Books and Jomo: How Gerakbudaya’s Pak Chong rebounded from 8 years of ISA

MALAYSIANSKINI | Bouncing back from years of being detained under the infamous Internal Security Act (ISA) is no easy feat.

Long-time detainee Tan Kai Hee of the Socialist Front took an entrepreneurial leap with Hai-O Enterprise Bhd and became a multi-millionaire and philanthropist who gave back to the community in many ways.

Others such as former PKR deputy president Syed Husin Ali and former DAP chairperson Karpal Singh resumed their political careers with some success, while others were still broken, having lost their health, purpose or means of living.

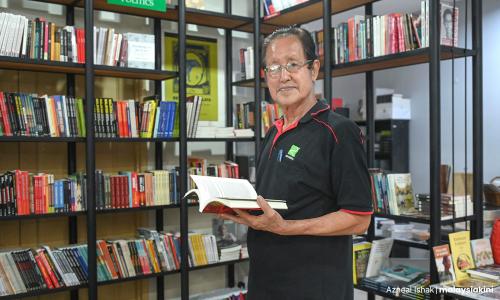

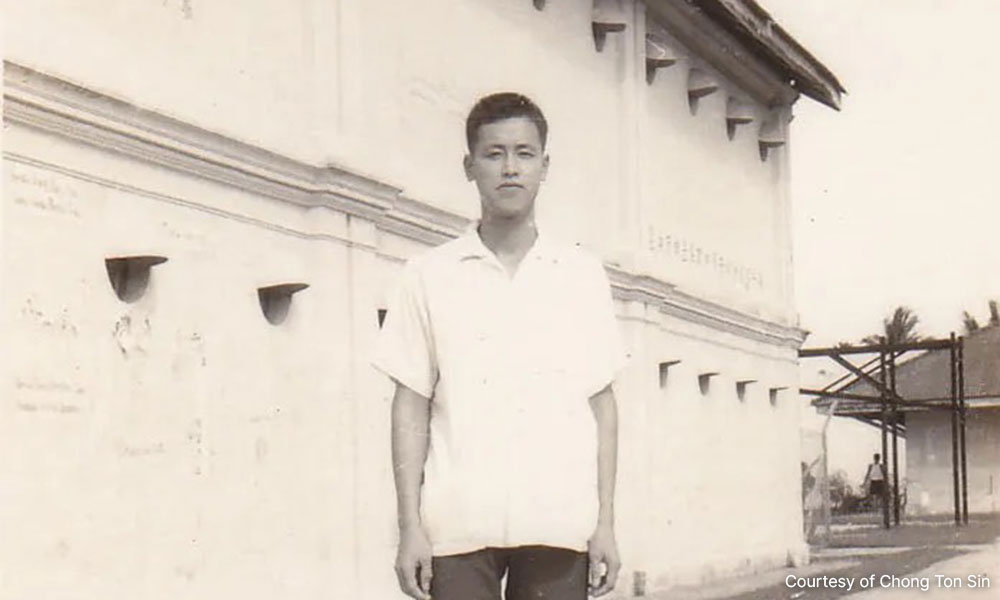

Chong Ton Sin, popularly known as Pak Chong, was detained at the young age of 20 in 1968 but maintains a surprisingly positive outlook over his eight years under detention.

The man whose name is now synonymous with progressive bookstore Gerakbudaya told Malaysiakini that he found a way to put his time under detention to good use.

Born to a nomadic family

Chong’s family moved around after leaving their ancestral home in Guangdong province in south China. His eldest sister was born in China, while the next four siblings were born on the Indonesian island of Riau. Chong and his two younger brothers were born in Johor.

“I was born in a place in Johor called Senai (on March 22, 1948) but when I was very young, we moved to Kluang where I grew up.

“Merdeka came when I was nine years old, but you could still see the British Army during the Emergency which ended in 1960, although the south part of Malaya was okay earlier.

“In those days, if you want independence, you are seen as anti-British of course. My siblings always talked about some friend in the jungle kena tangkap (detained) or shot dead. Both sides did the killing and ordinary rakyat could be trapped in the middle,” he said.

“We were lucky we were not in the New Village, you know, so we weren’t terkurung (confined). I grew up in Kampung Melayu where most of my neighbours were Malay,” added Chong.

He recounted how his parents worked as hawkers selling pau (steamed buns).

“In the morning, they’d sell near the checkpoint gates. This was normal. Many were also going to tap rubber. These are my memories of when I was little. I didn’t see or meet any communists, just listened to the stories only,” recalled Chong.

He spoke of the underground movements that existed in the underbelly of his school environment.

“I followed my parents and my brother to listen to ceramahs. I didn’t know what was being said (then).

“After Merdeka, I was a bit older and in the 1959 election, we supported the Socialist Front which had the Labour Party and the Parti Rakyat Malaysia (PRM). In 1959, Tan Kai Hee was one of the youngest candidates running in Kluang and we followed him.

“Nowadays, you can talk about such things, last time cannot.

“When I was in secondary school, there were underground organisations, they don’t say anything about parties, but they shared progressive books and had discussions. Mostly Chinese books talking about justice and labour rights.

“Chong Hwa High School in Kluang was quite popular and more and more people were interested in our activities. We had a night class and social gatherings,” said Chong.

Being a teenager, he was not directly affected by the ISA detentions that followed the outbreak of the Konfrontasi between Malaysia and Indonesia.

They saw virtually every elected MP, state assemblyperson and municipal councillor of the Socialist Front being detained in the early and mid-1960s. Among them were party leaders Ahmad Boestamam, Ishak Haji Muhammad and Abdul Aziz Ishak as well as other senior officials like Kampo Radjo, Kai Hee, Tan Hock Hin, Dr MK Rajakumar, Hasnul Hadi and Tajuddin Kahar.

The Socialist Front eventually dissolved under strong state repression and local council elections were abolished.

“The left-wing in Malaysia was destroyed by that. All the leaders went inside already but I was not detained then. I wasn’t afraid, of course, many people were scared but we knew it was to try and intimidate us. I was caught for a few days only at first. I think the situation made me like that. If I was one person alone, maybe I would be scared but there were many of us.

“At that time, every kampung got a Labour Party group, it was very active.

“My time to get caught was in 1968. I came out of school already. The Special Branch (SB) would keep tabs on student activists. The government was afraid of anyone who could be a leftist or a communist and the SB know you, they have their people in the school.

“So they go to school and tangkap (detained) 20 students. Some people confessed and named some names. Sometimes you simply say, but of course, I was involved. Not as a party member, but I did attend demonstrations and protests and put up posters,” he said.

To his surprise, his detention was constantly reviewed and extended, to the extent that he was detained from 1968 to 1976.

Time in detention

Chong’s detention was repeatedly extended but he recalled that at the time, political detainees were treated better than other prisoners.

“Sometimes we were detained for so long that even when the police said: ‘It’s time for you to keluar (go)’, some people didn't want to go home!

“I came from a poor family, the food I ate while in the detention camp was better than what I used to eat outside. I could study in detention, I read a lot, I could exercise, and I improved my Bahasa Malaysia and my English.

“I was first put in the Muar detention centre, and I was very happy as the grounds were very wide. I remember in detention I played football with the former PRM MP Karam Singh who was also under detention there.

“In Kamunting… I spent only two months. In 1973, it was full of old fresh air. No rooms, no walls. It was very good back then. But my final few years In Batu Gajah I wasn’t so happy - the space was too small,” he said.

Chong remembered that his father was positive, just advising him to study as much as possible while in detention, while his mother was a bit up and down, occasionally comparing him to his peers who were doing well outside.

Rebuilding with some helping hands

Chong said that it was very difficult to adjust to regular life after a long time in detention. Recalling his release in 1976, he said: “Many people who came out wanted to give up the political struggle. When they came out, the first thing was, do you want to get married or not? (For) many of us, our parents were old. Some people started businesses, while many did odd jobs like me.

“Another thing was that after 1969, things had changed. The Labour Party was gone, Parti Rakyat was very weak, workers’ unions and student movements also were suppressed, so even if you want to do something, it’s not easy.”

He said that for a few years, he too chose a low-key approach.

“I was also quiet. I didn’t join politics. I joined my brother in construction work and I moved around in Johor,” he said.

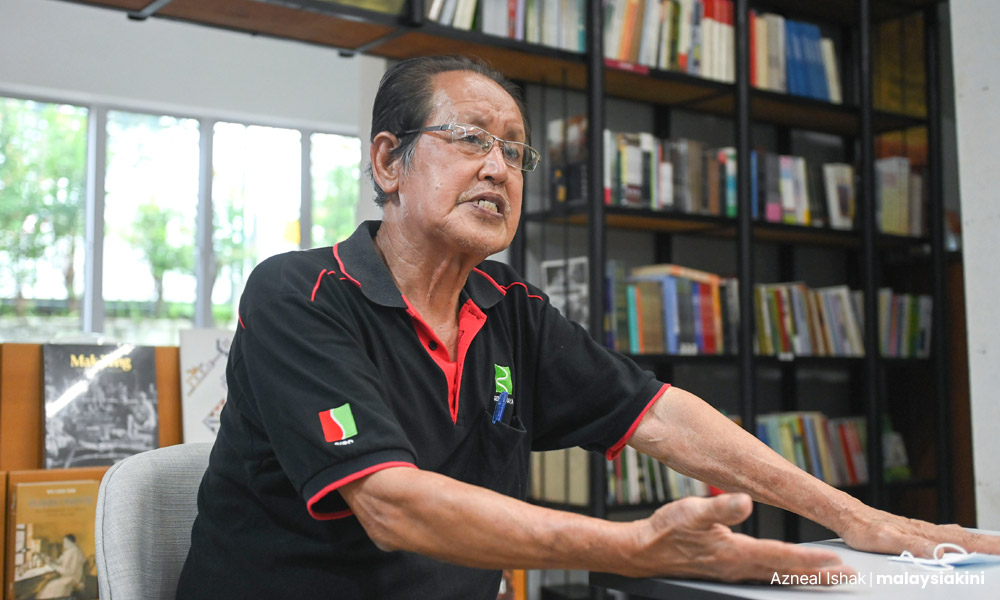

Chong said a meeting with academic Jomo K Sundaram played an important role.

“I met him in an unusual way. He was the editor of a magazine called “Nadi Insan”. It was a monthly socio-political magazine that featured articles in English and in Bahasa Malaysia, but was banned by Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s administration in 1983. I wrote a letter to the magazine and that’s how I met Jomo. Even now, we speak in Malay.

“Finally in 1985, I came to KL. I did some gardening work. I did some part-time work at Selangor Chinese Assembly Hall. When Jomo was inside the hall giving speeches, I would be outside selling his books from a car.

“Then I got used to selling books, publishing books, printing books. After that, I got involved with other books, not just Jomo’s books,” he said.

Chong was briefly detained at a protest during Ops Lalang, for one or two nights, in 1987.

“I was just married then (to The Star journalist Yap Leng Kuen). I didn't have a proper job or much income. She had to do a lot of freelance work, teaching, so it was a tough time,” said Chong.

In 1988, Chong went to Johor to support PRM deputy president Abdul Razak Ahmad in a by-election.

“In 1990, I also supported PRM president Syed Husin Ali who ran in Batu and I became active in the party until I was vice-president. But by around 2000, after the merger with PKR, I stopped to focus on my business,” he said.

Gerakbudaya today

Nestled in the leafy suburbs of Petaling Jaya, the impressive Gerakbudaya building has its roots in the heady Reformasi period at the turn of the century. The current premises was opened in 2014, prior to which he operated from a small space nearby.

“In 2000, I went to register the company. I had some investments and some shareholders, but not very much.

“The book business is not easy. There is a lot of censorship and intimidation. Not only the Home Ministry but the bookshops also were scared to carry our books. I always had to educate the booksellers not to be scared,” said Chong.

On June 30, 2020, police raided Gerakbudaya over “Rebirth”, a book that had a controversial book cover which featured an image resembling the national coat of arms and seized 313 copies of the book.

On Dec 18, 2020, the Home Ministry gazetted a prohibition order effective Nov 27, 2020, for the book “Gay is OK! A Christian Perspective” under Section 7(1) of the Printing Presses and Publications Act 1984.

But this year on Feb 22, the Kuala Lumpur High Court allowed the judicial review application by the book’s author Ngeo Boon Lin and its publisher Gerakbudaya Enterprise against the government’s ban over the book.

“For me, political issues are not such a problem. But legal suits like the one we are facing with the Sarawak Report are tough. The law needs to be changed because it punishes innocent people like publishers who don’t even know the content,” said Chong.

On Oct 31, Kuala Lumpur High Court will make a decision on the Terengganu Sultanah Nur Zahirah’s defamation civil action against Sarawak Report founder Clare Rewcastle-Brown for content included in her book 'The Sarawak Report - The Inside Story of 1MDB'.

This dates back to Nov 21, 2018, when the sultanah filed the civil action which named not only Rewcastle-Brown but publisher Chong and printing company Vinlin Press Sdn Bhd as well.

“I think things have improved over the years, but it’s still not very good. Nowadays the internet and social media make it open, but of course, people still make police reports so there are still challenges.

"I also don’t understand why they want to ban the book because people can exchange electronic copies very easily,” said Chong.

Gerakbudaya tomorrow

While the Covid-19 pandemic has generally weathered bookstores rough, Gerakbudaya - which had transitioned to the online sphere during this time - has emerged seemingly untouched.

Still, on average, Gerakbudaya churns out over 40 titles a year in various languages. In recent months, the local publisher has been in a prolific phase despite the recent challenges it has faced.

Titles include:

Arun Bala’s “Completing The Singapore Story?”

Murray Hunter And Lim Teck Ghee’s “Malaysia Towards GE15 And Beyond” and “Dark Forces Changing Malaysia”

“Life After: Oral Histories Of The May 13 Incident” by the members of the May 13 Oral History Group

Jeyaraj C Rajarao’s “My Odyssey: Revolutionary And Evolutionary”

“Sebutir Percikan: Biografi Chun Tae Il” by Cho Young-Rae

This is in addition to reprints of books by the likes of former Communist party of Malaya leader Rashid Maidin and UM professor Syed Hussein Alatas.

Chong said he is not so optimistic about the future of the book industry.

“People still read, but not books. Websites are enough, they don’t even want a newspaper. The e-book also still threatens physical books, so we have to adapt.”

“During the pandemic, we saw that outside bookstores closed. Because we are distributors also, we know that the industry is still going through difficult times,” said the Kluang native.

Chong himself used to write a lot of columns in the Chinese language but stopped when business demands grew. He said that during the lockdown, he began to write again.

When asked about his plans for the future, he laughed and said, “I’m old already lah! Maybe I look for someone to take over this business. If I cannot find (someone) after two to three years, I might have to close.”

Despite the many ups and downs, Chong is still keen that Malaysians do not give up hope in struggling for political change.

“I hope that Pakatan Harapan and others can see how to organise something and become strong. We cannot allow Umno and BN to regain their old power. We must create something new.

“Civil society must also be strong to keep politicians focused on the right issues. We must not lose hope. I remember a time when Malaysians thought that BN will rule forever, and the opposition will always lose but we know that’s not true.

“For the future, we cannot allow the old, dark forces to control Malaysia,” he concluded.

MALAYSIANSKINI is a series on Malaysians you should know:

Ernest Ng makes us laugh even at the worst of times

Joseph Gonzales lives for dance no matter where he is

'Riwayat' duo tells the Malaysian tale with new 'old' bookstore

The aunties and uncles watching over Muda

Emmy-nominated filmmaker Cheyenne Tan's stories about a better world

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable