'Tricks and cunning': Big penalties don't stop banks from moving dirty cash

Money streamed in from California, Peru, Bolivia, China and other places where low-income families were willing to sink their modest savings - US$2,000, US$5,000, US$10,000 (RM8,300, RM20,700, RM41,400) - into an investment they hoped would change their lives.

With the tap of a keyboard, money from investors were funnelled through the New York operations of global banking giant HSBC. Then it zipped across the world into accounts at HSBC’s sprawling Hong Kong offices.

Like others taken in by what became known as the World Capital Market (WCM) Ponzi scheme, Reynaldo Pacheco, a 44-year-old father in Santa Rosa, California, promoted the deal to family and acquaintances.

When the WCM scheme began to unravel, one of the unlucky investors Reynaldo had encouraged to put money into the deal decided to have him killed.

Three men kidnapped Reynaldo and beat his head with rocks, leaving him dead in a creekbed, his hands tied behind his back with tape and one of his shoelaces.

Thousands of victims lost an estimated US$80 million (RM331 million) in the scheme.

The FinCEN Files is an investigation by about 400 journalists across the globe, spearheaded by the International Centre for Investigative Journalism (ICIJ), involving bank filings leaked to BuzzFeed News.

The leaked documents were suspicious activity reports (SARs) filed to the US Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau tasked to collate and analyse transaction data to combat money laundering and other financial crimes.

The FinCEN Files show that HSBC continued shifting money for the WCM investment fund at a time when authorities in three countries were investigating the company and the bank’s internal watchdogs knew it was an alleged Ponzi scheme.

More than US$30 million (RM124 million) tied to WCM flowed through the bank in 2013 and 2014 — at a time when HSBC was under probation as part of its deferred prosecution deal with American authorities.

Even after US securities regulators won a restraining order freezing the company’s assets, WCM’s account at HSBC Hong Kong stayed active.

According to court documents later filed by attorneys seeking money for the scheme’s victims, WCM drained more than US$7 million (RM29 million) from the account during the following week, drawing its balance to zero.

READ MORE: US banks didn’t act on ‘suspicious’ Jho Low, 1MDB-linked transfers until too late, leak shows

WCM wasn’t the only company tied to criminal activities that moved money through HSBC during the five-year probation that came with the bank’s US$1.9 billion (RM7.87 billion) deferred prosecution deal.

An ICIJ analysis found that the bank’s Hong Kong office, for example, processed more than US$900 million (RM3.7 billion) in transactions involving shell companies. The companies were linked to alleged criminal networks in court records and media reports.

American prosecutors and other officials have praised deferred prosecution deals and other types of money laundering settlements as effective tools for making sure big banks follow the law and stop serving criminals.

A review of leaked documents showed dirty money flowed through HSBC’s Hong Kong offices - in one case, leading to a murder

When authorities announced Standard Chartered’s deferred-prosecution deal in 2012, an FBI official declared, “New York is a world financial capital and an international banking hub, and you have to play by the rules to conduct business here.”

ICIJ’s investigation shows that five of the banks that appear most often in the FinCEN Files — HSBC, JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered and Bank of New York Mellon — continued moving cash for suspect people and companies in the wake of deferred prosecution agreements and other big-money laundering enforcement actions.

Four of those banks signed non-prosecution or deferred prosecution deals in the past 15 years relating to money laundering. The only bank of the five that hasn’t been the subject of a non- or deferred prosecution agreement is Deutsche Bank.

Instead, Deutsche Bank reached a US$258 million (RM1.06 billion) civil settlement in 2015 in response to a probe by US and New York banking regulators that found that the bank had moved billions of dollars on behalf of Iranian, Libyan, Syrian, Burmese and Sudanese financial institutions and other entities sanctioned by the US.

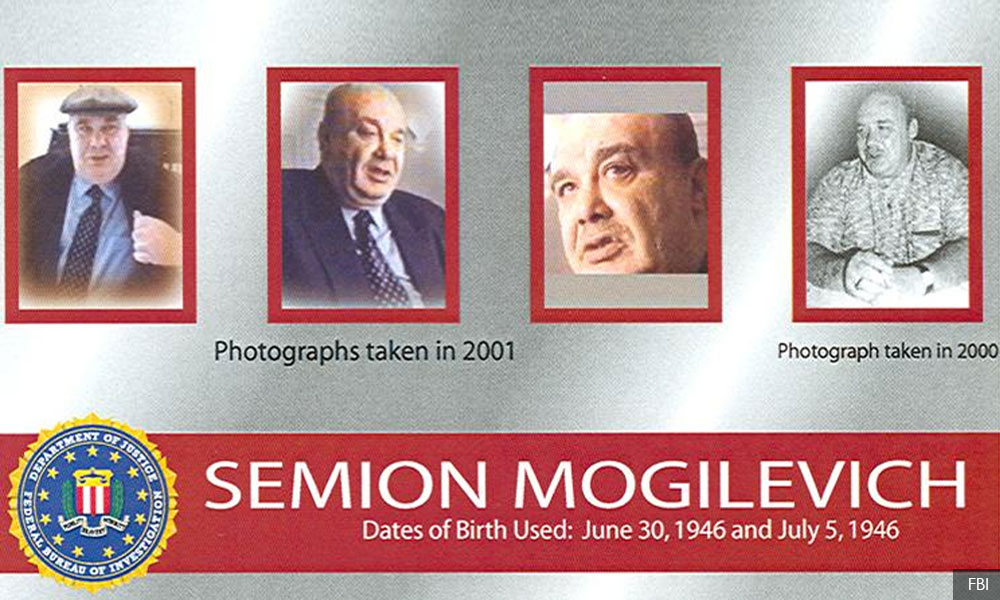

Semion Mogilevich, the alleged Russian mafia “Boss of Bosses” is believed to be behind transactions that got Bank of New York Mellon in trouble

Bank of New York Mellon was among the first big banks to pay a large penalty to US authorities for anti-money-laundering failures. In 2005, two years before its merger with Mellon Financial, Bank of New York paid US$38 million (RM157 million) dollars and signed a non-prosecution agreement after a federal probe concluded that it had allowed US$7 billion (RM28.96 billion) in illicit Russian money to flow through its accounts.

Media reports said investigators believed that Semion Mogilevich, the alleged Russian mafia “Boss of Bosses”, was behind some of the transactions.

Even as it has avoided big money laundering enforcement actions in recent years, Bank of New York Mellon has continued doing business with suspect figures, the FinCEN Files show.

The leaked records show, for example, that Bank of New York Mellon moved more than US$1.3 billion (RM5.38 billion) in transactions, between 1997 and 2016, tied to Oleg Deripaska, a Russian billionaire and a longtime ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Since 2008, Deripaska has been the subject of allegations in media reports tying him to organised crime. When US authorities announced sanctions against him in 2018, they said he was previously been accused of threatening the lives of corporate rivals, bribing a Russian government official and ordering the murder of a businessperson.

Deripaska denies laundering funds or committing financial crimes. In 2019 the Trump administration lifted sanctions on three companies linked to him. US sanctions on Deripaska himself remain and he’s suing in an effort to upend them.

“BNY Mellon takes its role in protecting the integrity of the global financial system seriously, including filing Suspicious Activity Reports,” the bank said in a statement.

“As a trusted member of the international banking community, we fully comply with all applicable laws and regulations, and assist authorities in the important work they do," it said.

Red Flags

One striking pattern revealed by ICIJ’s analysis of the leaked records is the willingness of multiple banks to process transactions for the same risky clients.

Deripaska, the Russian oligarch, didn’t just have Bank of New York Mellon helping him out. The secret records reveal Deutsche Bank shuffled more than US$11 billion (RM45.5 billion) in transactions between 2003 and 2017 for companies he controlled.

The records also indicate that Deutsche Bank and Standard Chartered helped Odebrecht SA — a Latin American construction firm behind what US prosecutors called the largest foreign bribery case in history — to move US$677 million (RM2.8 billion) from 2010 from 2016.

Deutsche Bank played a role in transactions involving more than US$560 million (RM2.3 billion) of that amount, the records show.

Then there’s Dmytro Firtash, a Ukrainian oligarch who is wanted on criminal charges in the US. In 2014, American prosecutors unsealed an indictment accusing him of bribing officials in India in an effort to secure a mining deal. Since late 2019, US news outlets have reported on claims that Firtash played a role in President Trump’s effort to dig up dirt in Ukraine on his 2020 re-election opponent, Joe Biden.

Firtash, who says he began his climb in business trading Ukrainian powdered milk for Uzbek cotton after the fall of the Soviet Union, lives in exile in a mansion in Vienna, protected so far from efforts to extradite him. His Art Nouveau villa has a home cinema and an infinity pool — a 2017 profile by Bloomberg Businessweek dubbed him “the Oligarch in the Gilded Cage.”

When it comes to banking, Firtash and companies tied to him found open doors among many of the industry’s big institutions.

HSBC, JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered, and Bank of New York Mellon continued to move cash for suspect people and companies, even after being fined for doing so.

All five big banks in ICIJ’s analysis — JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered, HSBC and Bank of New York Mellon — handled transactions for companies controlled by Firtash, the FinCEN Files show.

And the records indicate that all five banks had approved transactions tied to Firtash after US authorities had forced the banks to pay fines and pledge to work harder to vet suspect clients.

The files show that among these banks, JPMorgan moved the most money for companies controlled by Firtash by far — shuffling hundreds of transactions totalling nearly US$2 billion (RM8.27 billion) between 2003 and 2014.

JPMorgan and the other banks should have been aware of Firtash’s questionable history as far back as 2010, when a leaked US diplomatic cable linked Firtash to Mogilevich.

Then, in 2011, a lawsuit filed in Manhattan by former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko provided the banks even more of a heads up, even naming specific accounts at four of the banks that the suit alleged were being used by Firtash for money laundering.

The suit had accused Firtash, Mogilevich and future Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort of laundering illicit funds from Ukraine through banks and investment deals in the US.

The suit claimed that accounts at the New York offices of JPMorgan, Deutsche Bank, Standard Chartered and Bank of New York Mellon were being used in money laundering operations by shifting money stolen in Ukraine to the US and then — after it had been cleaned — round-tripping it back to Ukraine.

The lawsuit was dismissed in 2013, in part because Tymoshenko and her lawyers weren’t able to provide enough specifics of the transactions involved in the alleged scheme.

Firtash has denied wrongdoing, telling Bloomberg Businessweek that he’s the victim of “a special machine of propaganda organised against me”. He told the magazine that Tymoshenko was “wrong in everything. She lies all the time. In order to money launder, you need to have dirty money to start with. I always had clean money.”

In a statement, an attorney for Firtash told ICIJ that Firtash “has never had any partnership or other commercial association with Semion Mogilevich.” The attorney said Firtash would not answer questions from ICIJ because its queries are “reliant on the unlawful and criminal disclosure” of suspicious activity reports.

Holding bankers accountable

Why haven’t seemingly big financial penalties done more to change banks’ behaviour?

John Cassara, a financial crime expert who worked as a special agent assigned to FinCEN from 1996 to 2002, said that the size of the penalties paid by HSBC and other big banks may sound large but they’re actually a tiny fraction of the banks’ profits. And the money isn’t paid by the bankers who should be held accountable, he said — it’s paid by shareholders.

BNP Paribas, France’s largest bank, received the biggest fine of all in 2014, when it was forced to pay US$8.9 billion (RM36.8 billion) in the face of evidence that it helped shift billions of dollars through the US financial system on behalf of Sudanese, Iranian and Cuban entities, subject to American sanctions.

Unlike settlements with HSBC and others, this wasn’t a deferred prosecution. The bank agreed to accept a criminal conviction and to force out 13 staffers.

But for the French bank, the priority in settlement negotiations was ensuring that its licence to process dollar transactions in the US wasn’t permanently taken away. Instead, US regulators barred BNP Paribas from such activities for one year.

After the deal was announced, the bank’s share price rose four percent.

James S Henry, a New York-based economist, attorney and author who has been investigating the world of dirty money since the 1970s, said American enforcement actions over the past two decades have had some impact on large banks’ behaviour — at least compared to an earlier era when they operated with almost no restraints.

But he said it’s going to take “more prosecutorial will and international collaboration” to truly change the relationship between banks and illicit cash flow. That includes holding banks — as well as top bankers — accountable.

“We have to put some senior executives who are in charge of this stuff at risk,” Henry said. “And that means fines and/or jail.”

Shark Tank

It sounded like something out of a spy novel.

Deutsche Bank employees instructed clients from Iran and other hot spots to lace their payment messages with code words that would trigger special handling. One executive urged workers to employ “tricks and cunning” to avoid detection by American authorities.

These tricks of the trade were exposed in a November 2015 announcement by New York banking regulators. Deutsche Bank, state officials said, had been caught shifting nearly US$11 billion (RM45.48 billion) between 1999 and 2006 on behalf of Iran, Syria and other countries under US sanctions.

Under the US$258 million (RM1.06 billion) settlement with the state and the Federal Reserve, Deutsche Bank agreed to reform its practices and fire employees involved in the sanctions-evasion operation.

Deutsche Bank’s headquarters in Frankfurt, Germany. The bank says it has improved safeguards and is a different bank now.

In a statement, Deutsche Bank framed the deal as old news: “The conduct ceased several years ago and since then, we have terminated all business with parties from the countries involved.”

A month after the settlement was announced, the FinCEN Files show, Deutsche Bank was working behind the scenes to move money for a company linked to Ihor Kolomoisky — a Ukrainian billionaire who, US prosecutors later alleged, was engaged in a massive laundering scheme that funnelled cash into the American heartland.

Kolomoisky has his own spy thriller mystique. US prosecutors say he’s long been known for “ruthlessness and even violence” in business dealings, once hiring “armed goons” to take over the offices of a government-owned oil company.

In an article in the Wall Street Journal, one associate recalled meeting with Kolomoisky and watching as the oligarch pressed a remote-control switch that dropped crayfish meat to the hungry sharks occupying his office aquarium.

The leaked records show Deutsche Bank moved US$240 million (RM992 million) from December 2015 to May 2016 for a shell company registered in the British Virgin Islands that, US court filings claim, was controlled by Kolomoisky and a business partner.

A lawsuit filed last year in state court in Delaware alleged Kolomoisky used the shell company, Claresholm Marketing Ltd, to help pull off a “series of brazen fraudulent schemes” via PrivatBank, a Ukrainian institution that Kolomoisky and a partner controlled until the end of 2016.

The new owners of the bank claimed in the suit that Kolomoisky and his associates siphoned away billions of dollars from the bank through sham loans and then laundered the money through investments in the US.

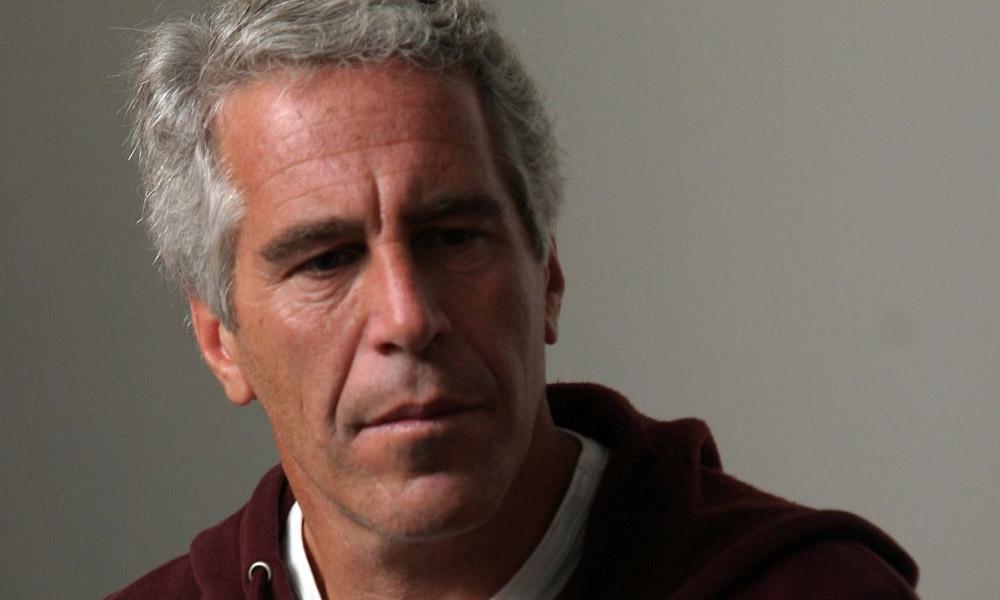

This past July, New York regulators reached another money-laundering settlement with Deutsche Bank. This time, the bank agreed to pay US$150 million (RM620 million) in penalties related to its dealings with convicted sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein (below) as well as with two non-US banks involved in money laundering scandals.

Deutsche Bank paid US$150 million (RM620 million) in penalties related to dealings with convicted sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein.

A month later, US prosecutors filed civil forfeiture complaints in the federal court in Florida that included allegations of thievery and money laundering against Kolomoisky, similar to the claims in the Delaware lawsuit.

Prosecutors said much of the money allegedly stolen from PrivatBank between 2008 and 2016 ended up in investments in the US — including commercial real estate in Texas and Ohio, steel plants in Kentucky, West Virginia and Michigan, as well as a cellphone factory in Illinois.

Kolomoisky did not respond to questions from ICIJ. A lawyer for him said in August: “Mr Kolomoisky emphatically denies the allegations in the complaints filed by the Department of Justice.”

In the state court case in Delaware, lawyers for Kolomoisky’s businesses said the suit failed to show violations of racketeering statutes or other laws. Kolomoisky has also filed a defamation action against PrivatBank in Ukraine, claiming the bank has falsely accused him of fraud and other wrongdoing.

Deutsche Bank declined to answer questions about its dealings with Kolomoisky, saying it was legally restricted from commenting on clients or transactions. The bank told ICIJ that it has acknowledged “past weaknesses” and “learned from our mistakes”.

It said it has “systematically tackled” these issues.

“We are a different bank now,” Deutsche Bank said.

Contributors for this story: Michael Hudson, Dean Starkman, Simon Bowers, Emilia Diaz-Struck, Tanya Kozyreva, Will Fitzgibbon, Sasha Chavkin, Spencer Woodman, Ben Hallman, Karrie Kehoe, Fergus Shiel, Kyra Gurney, Richard HP Sia, Amy Wilson-Chapman, Tom Stites, Joe Hillhouse, Delphine Reuter, Agustin Armendariz, Margot Williams, Hamish Boland Rudder, Antonio Cucho, Gerard Ryle, Mago Torres, Miriam Pensack, Scilla Alecci, Jelena Cosic, Miguel Fiandor, Michael Sallah.

The Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) is an independent international network of more than 200 investigative journalists and 100 media organisations in over 70 countries.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable