How to electorally marginalise the Malays

COMMENT | Given the vast electoral market of some 10 million Malay-Muslims (which should rise to 15 million before 2022), it is natural that many want to play communal champion or saviour for the Malay-Muslims.

Tragically, many of these Malay champions or saviours wannabes do not recognise what hurts the Malays. Sometimes, they even see bane as boon, defending old institutions or practices that are now marginalising the Malays.

One of them is malapportionment, the vast disparity of electorate size across constituencies, which traditionally triggers a polarised response along ethnic lines: applauded by most Malays and abhorred by most non-Malays.

Driven by communal self-interest, the polarised response towards malapportionment is based on two premises: (1) constituencies with fewer voters and hence over-represented are rural while crowded and under-represented constituencies are urban; (2) Malays are largely rural and non-Malays are predominantly urban.

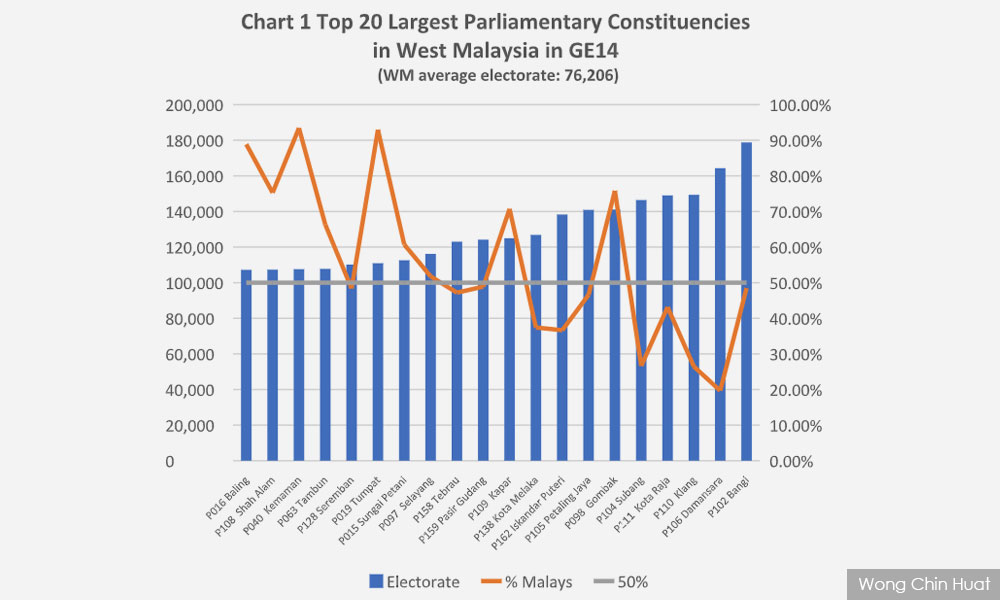

Here is the new reality based on GE14 data: Malays dominated 70% of the top 20 largest constituencies in Peninsular Malaysia. They were the majority in nine constituencies and a plurality over 45% in five others – Pasir Gudang (48.89%), Bangi (48.48%), Seremban (48.39%), Tebrau (47.19%) and Petaling Jaya (46.57%). (Chart 1)

With voting age at 18 (Undi18) and automatic voter registration, expect Malays to dominate 90% of the 20 largest constituencies in two years’ time.

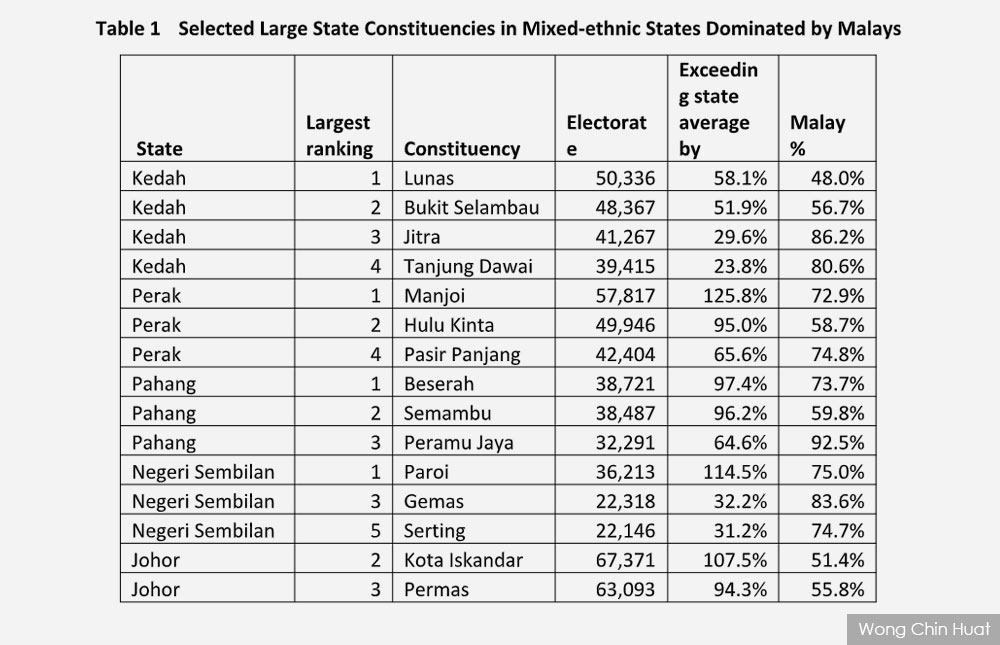

Similar patterns are found at the state level too, in multi-ethnic states of Kedah, Perak, Pahang and Johor. (Table 1)

Here are more facts to cause confusion if you believe that malapportionment is a neat communal game: non-Malays are occasionally beneficiaries of malapportionment too.

Pahang’s smallest parliamentary constituency, Cameron Highlands (32,048 voters in GE14) had a 66% non-Malay electorate: 30% Chinese, 15% Indian and 22% others. Johor’s smallest, Labis (40,356) was 45% Chinese and 15% Indian in composition. In Selangor, the second smallest state constituency, Sekinchan (18,101 voters, or 42% of state average) had a 53% Chinese majority.

Why doesn’t malapportionment favour Malays? There are two fundamental reasons why communal malapportionment – if once was largely factual – is now an outdated myth, with Malays as the largest victims in numbers.

First, Malaysia has undergone heavy rural-to-urban migration and rapid urbanisation since the 1970s. In 2018, 75% of Malaysians lives in urban areas. Given Borneo Malaysia’s lower urbanisation, the percentage in Peninsular Malaysia can only be higher.

So, who constitutes the majority of the urban population in Peninsular Malaysia if not the Malays? If Malays are the majority, how can you create large urban constituencies without marginalising the Malays?

Bangi is the best example. The largest constituency in entire Malaysia, with 178,790 voters in GE14 or 2.65 times the national average (67,300), it is a good example of a Malay-dominated metropolis.

With two public universities including the iconic UKM, here is home to Malay intellectuals and the middle-class. And more "Bangis" are in making if malapportionment is not arrested and reversed.

Second, malapportionment is strictly speaking a partisan enterprise, not a Malay nationalist project, even though Umno which drove malapportionment till 2018 packaged itself as Malay-nationalist.

Hence, malapportionment can benefit non-Malays when necessary – Cameron Highlands and Labis were MIC’s strongholds and Sekinchan was once MCA’s territory.

More interestingly, Malays can be targeted for being in the wrong camp. In the 2003 delimitation exercise, the sleepy town of Baling which voted PAS in 1999 was made Kedah’s second-largest parliamentary constituency with 72,387 voters. Meanwhile, state capital Alor Setar was drawn to have only 56,007 voters.

In GE14, Baling (107,213) continued to have more voters than Alor Setar (80,272), and the gap had grown from 12,380 to 36,949. Is Baling a metropolis bigger than Alor Setar? What rural weightage in malapportionment are we fooling ourselves with?

Malays can also be made a political sacrifice for a more intriguing reason: gerrymandering. In urban areas where support for Umno was low and scattered, constituencies like Pasir Gudang, Tebrau or Tambun needed to be big to gather enough Umno voters.

The oversized constituencies dominated by Malays are very much rooted in interstate malapportionment or unequal allocation of parliamentary seats across the state.

Back to Chart 1, half of the top 20 largest constituencies are from Selangor. This happened not just because the Elections Commission (EC) had divided Selangor into 22 parliamentary constituencies of vastly uneven sizes – from 178,190 in Bangi (the largest) to 40,863 in Sabak Bernam (the smallest).

Had the EC delivered equal apportionment, every parliamentary constituency in Selangor would still have 109,776 voters while a Pahang constituency had only 58,856 voters.

In 2003, Parliament gave Selangor 22 seats and Pahang 14 seats, even though Selangor had 2.5 times the number of Pahang’s voters. By GE14, higher population growth had made Selangor’s electorate three times Pahang’s, but both states kept their respective 22 and 14 seats.

In normal countries, where parliament’s size is fixed, seats will be transferred from shrinking states like Pahang to expanding states like Selangor. This normal process is called reapportionment.

In Malaysia, politicians and voters, however, develop a sense of entitlement that constituencies once created cannot be taken away.

How do we correct malapportionment that marginalises Malays if we continue to reject reapportionment? The only alternative to reapportionment is seat increase.

From 1965 when Singapore left Malaysia to 2005 when parliamentary seats were last added, Malaysia’s parliament has expanded by nearly 50% in size, from 144 to 222.

As the trend of immigration from states like Pahang to states like Selangor will not stop, are we going to expand our Parliament indefinitely? Some would jump at reapportionment, seeing this as a conspiracy to dilute the Malays’ political power.

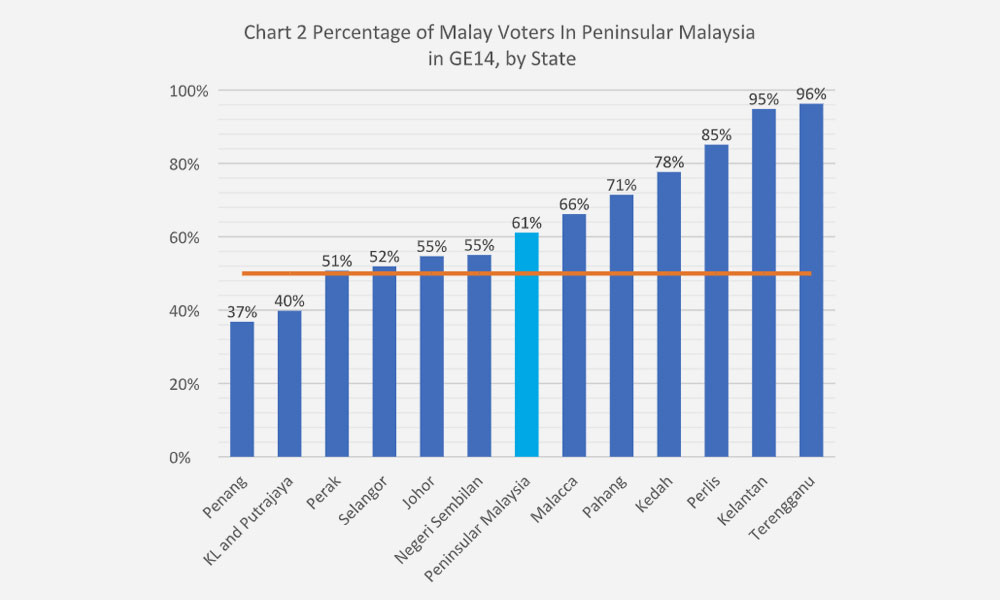

Here are the facts to those who live in the past: by GE14, Malays were the majority in all but two Peninsular states/territories. (Chart 2) Malays would dominate all Peninsular states/territories including Penang and Kuala Lumpur when the eight million new voters enter the electoral rolls in two years’ time.

The losers in malapportionment are the Malays in supersized constituencies like Bangi and Shah Alam, urban centres that attract migrants from states like Pahang as well as from rural Selangor towns like Sabak Bernam.

When parliamentary seats are kept in shrinking states like Pahang, ultimately it is the children and grandchildren of Pahang Malays that get politically marginalised.

Likewise, when Sabak Bernam enjoys disproportional electorate power, children and grandchildren of Sabak Bernam Malays who move to Bangi and Shah Alam pay the price.

Do all urban Malays lose out? Of course not. The losers in Shah Alam would be the B40 Malays working in the Batu Tiga factories, not the "Datuks" and "Tan Sris" in Section 9 who influence policy decisions on the golf course instead of in the polling booth.

Malapportionment is essentially political inequality. With Malays now the dominant majority in Peninsular Malaysia, the bulk of losers are no longer non-Malays but ordinary Malays “without cables” in the urban centres.

Where are the Malays’ champions and saviours on this?

Related article:

Might Undi18 disempower the youth?

WONG CHIN HUAT is an electoral system expert at Jeffrey Sachs Centre on Sustainable Development, Sunway University. He also leads the clusters on electoral systems and constituency delimitation as part of the government’s Electoral Reform Committee (ERC).

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable