Drawing the virus out: Making queer art on my own terms

COMMENT | In December 2015, I was asked to resign from my post as manager of a prominent commercial art gallery in Kuala Lumpur, three months after starting work, ostensibly due to the fact that my employer discovered I was HIV positive, a condition that I myself only found out during the health screening procedure required by the company when I joined it.

From my experience as an LGBT rights activist, I knew that Malaysian employees are not protected by law from discrimination based on their HIV status. I figured that legal recourse against a large corporation would end up being a costly and lengthy process, something that I didn’t want to go through.

Not wanting to continue working in what I perceived to be an unsupportive work environment, I tendered my resignation.

What followed in the two years since has been a difficult personal reassessment of my life, coming to terms with the real and perceived HIV stigma, finding support in unexpected places, undergoing therapy, and using art as a way to reinvent my identity.

Shock treatment

Right after my resignation, I began antiretroviral therapy in January 2016, receiving care from Sungai Buloh Hospital, where most newly diagnosed HIV patients based in Klang Vallery get initial treatment.

The hospital visits were, in the beginning, a stressful affair. The nurses seemed inundated by the number of new cases that flooded into the hospital, resulting in long waiting periods – my first visit lasted six hours, most of which was spent on waiting for my number to be called. I soon learned to bring a book with me, to alleviate the anxiety of waiting for needles and medication.

While working, I had been able to afford to live a comfortable middle-class lifestyle. But after resigning, money became a real issue. In hindsight, I should have looked for a job. But in the emotional state I was in, I was not prepared to receive another round of workplace discrimination.

Perhaps I was wrong to expect assistance and support from my friends, but that was exactly what happened. And when that was not forthcoming, I decided, in my audacity, to forgo my qualifications as a trained writer to become a full-time artist.

Ultimately it was a decision that, for better or worse, allowed me to retain some measure of self-worth. Self-worth that also mocked the downgrading circumstances of my life – forced by my dwindling savings to move from a relatively affluent neighbourhood to an apartment sponsored by a friend in a working-class area, where the impoverished surroundings only reflected how much I had fallen from grace.

The move also isolated me from my social circle. As a person who was proudly out and bourgeois, I experienced what was essentially a riches-to-rags, hitting rock bottom reality check scenario, fuelled by increasing bouts of depression, frustration and disappointment.

It wasn’t a situation I thought that I would ever experience as I entered my 40s. Nevertheless, I was adamant about pursuing the one thing that I thought could redeem me: art.

Although I have no formal training in art, I’ve been casually pursuing my art practice since 1998, in tandem with my other life as a self-taught musician and poet. Out of the three mediums, however, making art turned out to be the perfect medium for me to articulate what I was.

I couldn’t sing or write about the virus that was inside me, but somehow I could draw it out. And that was what I did.

From March 2016 to December 2017, I created five different but related series of artwork.

From cats to talismans to humans

The first was Catological, a series of 16 somewhat ludicrous watercolour paintings based on the topic of cats that I thought at the time would be a lucrative topic for sale at Art For Grabs, an arts and crafts fair where I had successfully sold my work before.

To my astonishment, I managed to sell all 16 pieces. Spurred on by the success of Catological, I decided to give myself a more ambitious assignment: work on a series of paintings that I could mount a solo exhibition around.

That led to the development of a series of works based on the human figure. While I have drawn human figures previously, I decided, based on my experience as a manager of an art gallery, that I would put more thought and care into developing this new series.

This included putting in a period of studying the figure painting in the history of art and developing my own style and technique. Little did I know then that it would result in a year-long pursuit.

While I slowly worked to develop the as-yet-untitled human figure series, I decided to create another one which would have a more immediate impact. This would result in Talismans.

In the first iteration of Talismans, I decided, with my sister’s help, to create mini-cushions that doubled as keychains and fridge magnets. On these mini-cushions, I painted various obscene, taboo, and suggestive words. These I managed to successfully sell at the next Art For Grabs.

I hadn’t realised it at first, but Talismans awakened me to how inherently queer my art practice was and could be if I decided to pursue it further. Even the simple act of putting a queer signifier such as the word “pondan” (roughly translated as a sissy, or effeminate or gay) on a somewhat innocuous and banal object as a squishy keychain and fridge magnet-cushion could be a transgressive act. It made me realise I could think more queerly about my human figure series.

The most successful talisman object was Siti Kasim's Middle Finger, which referenced an incident in which prominent Malaysian human rights lawyer and activist Siti Kasim flipped an obscene gesture at a forum when she was confronted by religious conservatives.

I loved the rebellious, defiant gesture – which created a media controversy labelling her as indignant – and embraced it as an act of queer transgression in a cultural milieu that values conformity and conservatism over individuality and freedom of expression.

The Talismans series also led me to think about painting on non-traditional mediums, specifically to an offshoot series I decided to title Epic Understatements, which were novelty boxer shorts with handpainted designs coupled with cheeky statements. These were also successfully sold at yet another Art For Grabs.

Depression and catharsis

By December 2016, despite managing to sell some artworks and securing part-time work as an archivist for a website, I found myself struggling to make ends meet, even though I needed only about RM1,000 per month to live on.

I applied for a year-long arts residency and was hoping to be accepted so that I could develop my work, but unfortunately, my submission was rejected. This was a big blow, but I persisted.

At times it seemed as though I was working blindly, not knowing if I ever could get an opportunity to fully realise the work.

A chance meeting in December 2016 with curator Sharmin Parameswaran changed all that. While developing my art, I had been co-organising Rainbow Rojak, a monthly series of queer social nights I started in 2013 that was aimed at providing a safe party space for LGBT youths and their friends in the Klang Valley. Sharmin had been a regular attendee of these parties.

Upon discussing my work with her, she became interested to see it, after which she decided to collaborate with me on my solo exhibition. But it wasn’t all smooth sailing.

In June 2017, I had my worst bout of depression. For three weeks I had an overwhelming feeling of fatigue. I could just manage the basics of self-care but was unable to engage with others.

Thankfully, my friends cared for me and encouraged me to seek professional help. Two months of therapy followed.

Mostly, therapy helped me with dealing with the aftermath of my diagnosis and subsequent change in lifestyle. It also helped with reaffirming the decision I had made to pursue my art practice, which, although it provided barely enough in terms of financial remuneration, did contribute to my sense of self-worth.

It turned out that art and friends saved me, and therapy helped me recognise that, in spite of everything, I was still in charge of my life.

My therapists Karen and Jo were also open to looking at the work and discussing it in more personal terms, which helped me open up more about my process. I discovered that, yes, the key to opening up the work so that others could relate to it was to make it queer, affirming what has been my approach to life and art.

Making queer art

How does one make queer art? It’s a question I’m still trying to figure out. But I draw on my experience as a co-organiser of queer events, including Seksualiti Merdeka and Rainbow Rojak; interactions with other queer individuals within the community, especially the trans artist Shika and drag queen Shelah (performed by Edwin Sumun); and my own personal experience as a cis gay man who has never identified with the gay community.

I don’t identify with the gay community because I reject the mainstreaming, sanitising and dilution of queer concerns, issues and identities. This disempowers and displaces the LGBT community as a whole.

It’s my personal belief, that queer transgression although it should remain open to discourse, must be loyal to what makes it different from the heteronormative. But how to translate these ideas visually, in a way that can be accepted in conservative and heteronormative Malaysia, without resorting to verbose queer-speak?

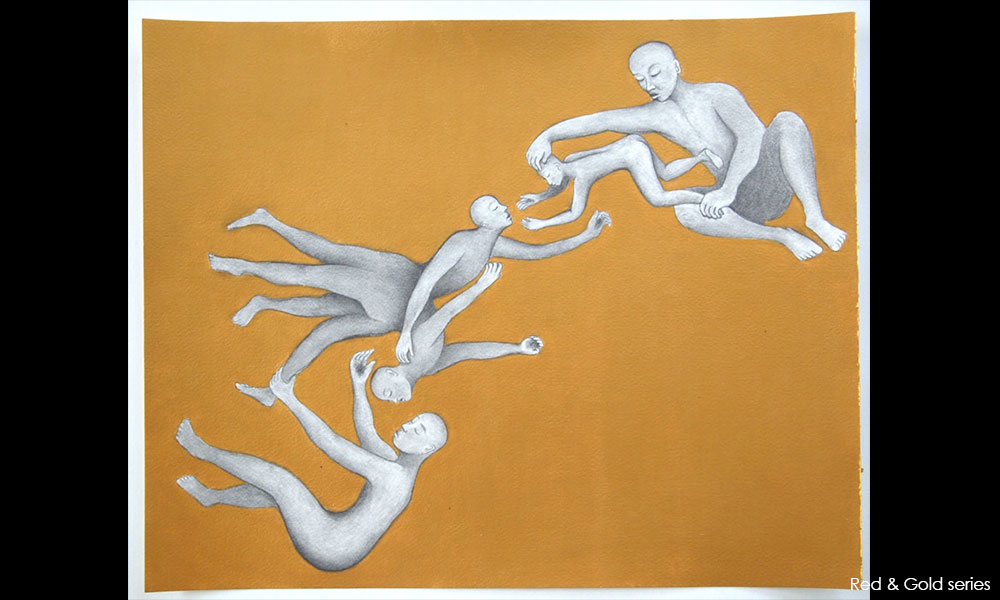

I chose to address the erasure and ambiguity of identity: one of the key aspects of my depictions of the human figure was that although they are nude, they lack obvious gender signifiers: no breasts, no genitalia, no body hair.

Although this androgynous quality is not always adhered to, I was very aware of how the bodies are perceived.

By removing genitalia, I wanted viewers to look at the bodies in a non-gendered, non-erotic way, to see the body as a symbol, or metaphor upon which a post-feminist queer reading could be projected.

By removing something, it makes it more obvious that it’s not there.

I wanted the bodies to be languid, open, revealing, but still maintaining an air of dignity and mystery. I found that it helped viewers to also view the figures with less prejudice; challenging the nature of their gaze by acquiescing to it.

But the series is not a total rejection of the more scatological aspect of the human body. In the end, after experimenting with different colours, I chose to limit my medium to pencil for the human bodies as a play on my personal “drawing” out of the body.

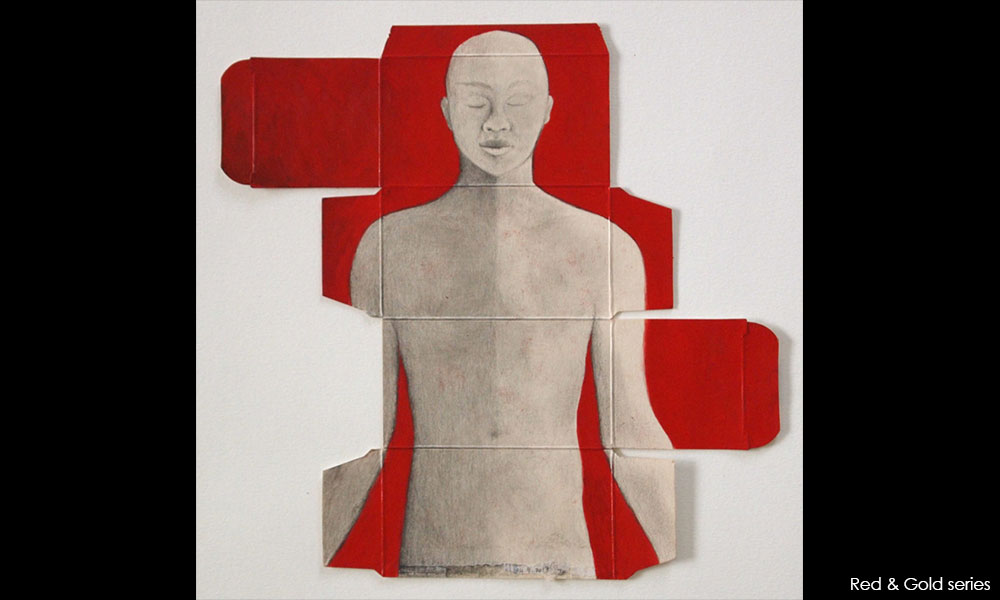

I also limited my colour palette to red and gold pigments, in order to make metaphorical allusions to blood (life) and urine (death), which also helped to unify the works visually. The exhibition, which was staged at Raw Art Space, KL, was titled Red & Gold.

In some of the works, inspired by the use of non-traditional mediums in the Talismans series, I decided to paint some of the human figures, and also a few text-based works, on the back of my HIV medication packaging.

I’m still not sure why I did this; perhaps it was an act of reclaiming some of my life back from the virus that has come to define the past two years of it. These works were the most meaningful to me personally.

The Red & Gold exhibition also served as my farewell of sorts to the city of Kuala Lumpur, where I had lived since 2000. It was a bittersweet end. I wished it wasn’t so. But I had to leave for reasons practical, as well as emotional and psychological.

The healing continues

As I write this, I’ve been back in my hometown, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, for two months now, resettling with my family.

One of the main reasons for my moving back is to spend time with my 77-year-old mother, who is living with Type-2 diabetes and is also a survivor of cancer, stroke and amputation. She’s in good health for now, but needs constant assistance, and I’ve decided to come home to help my family with her caregiving. The doctors have ruled out surgery and chemo, so she’s basically in semi-palliative care.

I’ve been able to pursue my art practice in isolation, working from a small studio in a corner of the family home. Although superficially the studio looks nice, and my living conditions have improved, thanks to my family’s rent-free generosity, I don’t think my subject matter has gained much levity.

In a way, I think it’s had to deal with even more interesting subjects such as decay, ageing and the even more conservative - yet less codified way of life in Sabah - all this compounded by the fact that I have chosen to hide my HIV status from my family.

But it’s a challenge I’m willing to take on for now because it would be interesting to see how my art practice will ultimately be affected.

JEROME KUGAN requests not to be tagged when you share the article. Thank you. This article was originally published in Queer Lapis.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable