Understanding economic insecurity

COMMENT | Nearly 30 percent of Malaysians polled by Gallup in 2018 felt that they did not have enough money for food, while 23 percent reported not having sufficient money for shelter.

These are two very essential measurements of economic security or the lack of. These are shocking and scary figures for anyone who cares about the social cohesion of a society.

There are two points to note on this matter. For starters, such a situation did not happen overnight and its causes go way back beyond the time Pakatan Harapan took over in May 2018. These are structural issues stemming from the Asian Financial Crisis, pushed to breaking point by the sixth prime minister Najib Abdul Razak’s kleptocracy and profligacy.

Second, if we don’t face up to the country’s deeper and long-term economic challenges, measures taken by us risk amounting to a mere reshuffling of chairs on the deck of the Titanic.

While most Malaysians describe the current economic woes as a “cost of living” problem, it is a not-too-hidden crisis that up to 80 percent of Malaysians are experiencing economic insecurity through a number of factors, most important among which are low wages, cost of housing and cost of transport.

To deal with economic insecurity, we will have to acknowledge that the economic model that got us here has reached its limits and there is a dire need to break free from the conceptual hold of old ideas with a new paradigm. The trouble is that we will have to do all these amidst global headwinds.

The cost-of-living debate: A brief history

The cost-of-living debate is essentially a shorthand to describe collective economic insecurity.

The World Bank must be commended for its latest Malaysian Economic Monitor (MEM), which is themed “Meeting Ends Meet”. In summary, the World Bank is saying that “cost of living” is a catchall shorthand that means very little in public policy terms.

The analysis in this MEM has shown that overall price inflation is not currently a major contributor to the high cost of living in Malaysia.

The World Bank suggests that four conditions need to be looked into, namely:

- Living costs and prices vary across geographical regions;

- Income is simply way too low;

- Households are consuming through debts; and

- Housing prices are beyond the means of most families.

I first met Ibrahim Suffian of Merdeka Center in 2003, when he had just started tracking public sentiments in Malaysia. In all polls that Ibrahim did throughout these years, “cost of living” has consistently surfaced as the top concern of the people polled.

During my first election debut in Bukit Bendera, Penang, in 2008, we started each of our grassroots walkabout campaign by saying that "BN stands for Barang Naik (prices going up)" since the petrol price hike in 2006 and inflation as a result of the global commodity boom was painfully felt by citizens in urban areas. The irony was that the suburban areas that lived on palm oil production were doing reasonably well because of high commodity prices.

After losing the two-thirds majority and five states on March 8, 2008, the fifth prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi was badly advised to increase petrol price by 40 percent on June 4, 2008. This effectively signalled the beginning of the end of his time in power. Abdullah succumbed to a putsch led by Najib in September 2008, and he announced that he would retire in April 2009.

Much as the fall of Najib in 2018 was attributed to the 1MDB scandal, the steep austerity drives in 2015 and 2016 (more than 30 percent cuts to budget allocations) in response to the fall in global oil prices (in effect a revenue crunch), the implementation of the goods and services tax (GST) in April 2015, and the lack of economic opportunities for ordinary Malaysians, played a huge part too.

The 30 percent depreciation of the ringgit since October 2014 also contributed to higher prices of imports. Of course, the icing on the cake was when the public witnessed the extravagant lifestyle of Rosmah Mansor, which reminded them of Marie Antoinette.

At the heart of the matter, "Najibnomics" had no empathy for the small guy and no holistic understanding of economic insecurity of a large part of the population that required broad-based and massive reforms to solve.

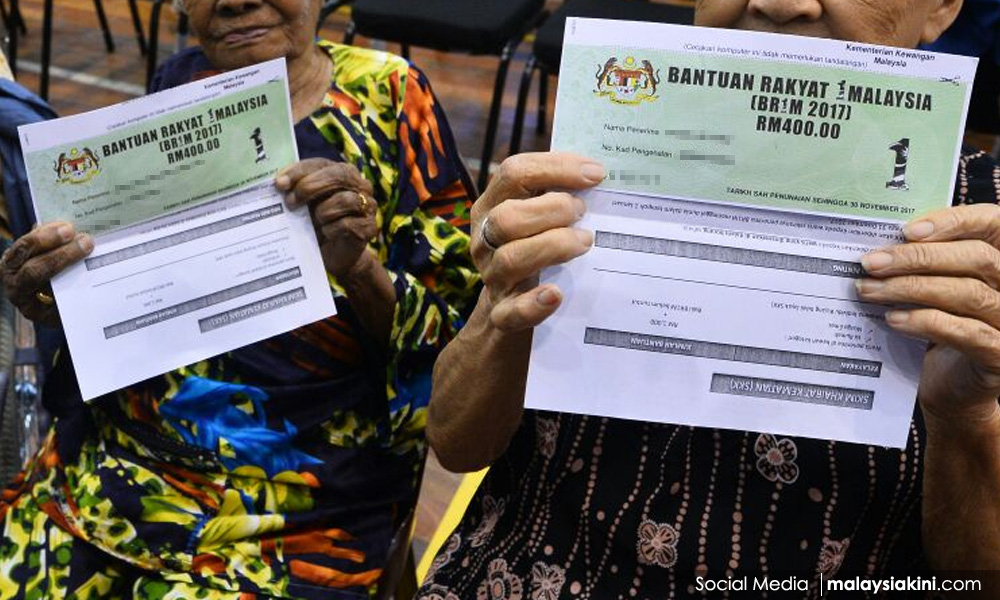

Najib compartmentalised his thinking into "capital economics" and "people’s economics". In short, for him, the objective of an economic policy was to serve the interests of those who owned capital, and where the rest are concerned, he simply gave them cash handouts - such as BR1M. “Empowerment” also doesn’t enter his lexicon.

These are lessons for us in Pakatan Harapan to learn, and to learn humbly and deeply. Economic security in its holistic sense better describes the problem at hand than the cost of living shorthand.

Understanding insecurity beyond B20 and M60 labels

In many ways, up to 80 percent of Malaysians live with economic insecurity, in different degrees and extent, but having similar concerns.

The World Bank report made the point that there is a difference between the B20 group and the B21-B40 group. Recently, Professor Jomo Kwame Sundaram (and Khazanah Research Institute's Hawati Abdul Hamid) have argued that members of the large B70 group have very similar social and economic needs. These are calls for us to reconsider our basic policy terminology.

In 2011, the budget committee of Pakatan Rakyat, myself included, argued that the economy must give the bottom 60 percent more disposable income through better jobs and better pay. This would enable the entire economy to benefit from sustainable growth driven by consumption that is not fuelled by debt.

The Najib government, however, went for the band-aid solution of cash transfer to 60 percent of the population and introduced the BR1M in the 2012 Budget.

If we consider the B20 group, in the light of the United Nations report written by UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Professor Philip Alston, which suggested that Malaysia’s poverty rate is most likely to be between 16 and 20 percent, it appears correct to conclude that the B20 group as a whole are poor by most definitions.

Beyond the B20 group, the rest of the population - perhaps excluding the top 20 percent, - the middle 60 percent (B21-B40, M40) are almost in the same boat.

The government should, therefore, rethink the poverty rate definitions suggested by the United Nations and move away from the B40-M40 dichotomy that is now looking like a rather meaningless distinction.

The M40 is not the “middle class” that one might imagine. They essentially face the same problems as the B21-B40. They have middle-class aspirations, but they oftentimes have difficulty reaching the idealised status of the “middle class”.

A recent Khazanah Research Institute report pointed out that about 20 percent of the M40 is misclassified because the household size was not accounted for. A household officially classified within the M40 income class but having many familial dependents, shares similar financial burdens as the B40 class. Our statistics understate the financial hardships of a substantial number of ordinary Malaysians.

These labels have serious material and policy consequences, which is why we need to discuss and consider them carefully, instead of imbibing them uncritically. In official circles, there is a tendency to see the B40 not only as “poor” people, but also as passive people who lack agency.

If we make such an assumption about them from the very start, we will end up assuming that giving some token handouts to these “poor” souls is enough to solve the problem. Najib ended up giving 60 percent of Malaysian households BR1M, which was actually a back-handed admission that 60 percent of Malaysians didn’t live well under his watch.

Najib and his team weren’t thinking straight when they proposed the implementation of GST. You can’t be giving handouts to 60 percent of the population and then want to tax them through GST, which taxes those who do not qualify to pay direct tax. It was badly advised. Taxing people who do not have enough for food and shelter is a sure recipe to invite trouble.

The B20 poverty category, as defined by the United Nations, needs welfare, but in the Malaysian context, it appears that the subsequent 60 percent – let’s call them M60 for convenience – need better jobs, better pay, better business opportunities, better upward mobility for their children, better housing options and better transport alternatives.

What this means for policymakers is that a national economic policy at this time needs to empower a large segment of the population if the country is not to deteriorate, with a majority of our people living with a very deep sense of economic insecurity.

A paradigmatic shift is needed.

Here lies the shift in hard policy thinking and communications that the government must embark on in the months and years ahead to bring the nation to the next stage.

When there is heightened economic insecurity across a vast segment of citizens, any adverse headwinds, small or big - such as a trade war, another economic crisis, or the start of a monetary tightening cycle, a fall in the ringgit, or a cut in subsidies - would cause panic and uproar.

To recognise that up to 80 percent of our citizens face some form of economic insecurity, and to intervene from this basis help prevent systemic failures, such as the massive revolts recently seen on the streets in South America.

The Malaysian state has always maintained a significant level of intervention in the economy. This is good since it reflects a conviction that not all things should be left to the markets.

The state holds the responsibility in reining in the excesses that markets, as a rule, are prone to. This responsibility is easily misused though, once the state is captured by vested interests or maybe inertia.

I had an interesting chat with a tycoon recently. To my utter surprise, he, of all people, suggested to me that the government should start thinking about providing free housing for the needy.

I probed him further, and it turns out that his point is this - all governments will have to think ahead to prevent economic revolts of the type that have happened on the streets of Chile and in other South American cities, and in Hong Kong.

He reasoned that the economic system must either pay workers more or it must reduce the costs of housing and transport. To him, it is better for the government to pay for housing through taxes, than for businesses to try to raise salaries fast enough to contain discontentment and despair.

Of course, at some point, the tycoon should pay a bit more tax, which he knows it, as a means to keep the economy away from systemic failure.

Put more neutrally, the way our economy organises the dynamics of wages, housing and transport will have to change to make most Malaysians feel more secure.

Note: This is the first of a three-part essay on economic security

LIEW CHIN TONG is the deputy defence minister and DAP national political education director.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable