Education report card - we could much better

COMMENT | As another protest gathering of the major Chinese associations hovers over the introduction of khat calligraphy in the vernacular school curriculum, the Education Minister gleefully prides itself as the first ministry to present its “report card” for 2019, themed ‘Education for All’: “We have targeted 2019 to be a strong foundation year to ensure the country can move towards an inclusive and high-quality education system,” he said. He even prided himself with the achievement in fulfilling the promise contained in the Pakatan Harapan manifesto on the issue of the National Higher Education Fund Corporation (PTPTN) education loans and the recognition of the Unified Examination Certificate (UEC).

One wonders whether the education minister is living inside a delusional bubble when he says Harapn has solved the problems involving PTPTN loans and the recognition of the UEC. How have the PTPTN loans been solved? And if the UEC has been recognised, could he please announce it straight away because it will certainly be the headlines in tomorrow’s Chinese press.

Instead, the headlines in recent days concern the big protest gathering of the major Chinese associations (set for Dec 28) against the introduction of khat calligraphy in the vernacular schools’ curriculum – a most unwelcome attempt by the education ministry at an “inclusive” education system.

Let me remind the public that the last time there was such a big protest by the major Chinese associations was in October 1987 against the sending of non-qualified administrators to the Chinese primary schools. It emerged that this directive was in fact orchestrated by the “deep state” to provoke the launching of ‘Operation Lalang’ and thus rescue Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s Umno "Team A" by sacking the then Lord President and three Supreme Court judges who were about to judge the case brought by Umno's "Team B" against Team A. I was one of the 106 hapless victims of Mahathir’s ruthless ISA operation and that is why this looming protest brings back more than an ominous whiff of déjà vu.

While he promises education for all, the education minister has, since his appointment, consistently failed to bring about the promised education reforms that Harapan promised in their GE14 manifesto. The latest diversion to introduce khat calligraphy in our primary school curriculum has led to an uproar in the non-Muslim communities even before the UEC controversy has been settled. Incidentally, the Council of Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity, Sikhism has also opposed this proposal to introduce khat calligraphy in the primary school curriculum because of its Islamic undertones.

The stated aim of inclusiveness in our education system should not simply be a phrase for appeasing Malaysian minorities; it embodies the important principle that for our education system to be on par with the best in the world by 2025, it must be secular in philosophy and practice. Thus, a progressive school system would respect all pupils equally and teach in a neutral and objective way about the different faiths that people have.

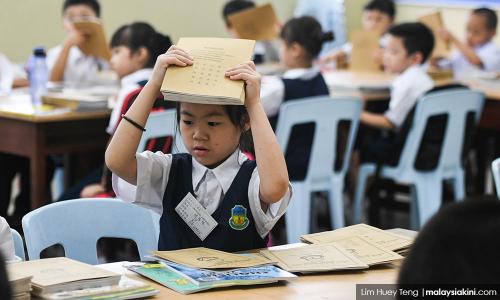

The role of Malaysian schools is to bring diverse children together and teach them subjects that have a basis in scientific fact, like mathematics, languages, geography, history and critical thinking. These provide the knowledge and skills that are vital to their performance in the global achievement indices, TIMSS and Pisa that the blueprint benchmarks.

Progressive education is about co-creating the stimulating conditions, such as through literature, music and nature through which “character” is built rather than through didactic moral education and encroaching on religious forms.

The Malaysian Education Blueprint acknowledges that education standards in the country have deteriorated so seriously that we have fallen into the bottom third amongst countries in the global indices that measure achievements in maths, science and other such basic competencies. Our achievements have even fallen below that of Thailand! Although there is an improvement in our 2018 Pisa ranking, we are still below the overall average in the OECD ranking.

We don’t need a genius to tell us that education reform has to work in tandem with badly needed economic and human resources reform. Apart from falling behind our Asean neighbours at the SEA Games, we are rapidly falling behind Philippines and Vietnam in the economic league table. When are we ever going to boost productivity with the practical inclusive strategies like collaborating with our workers’ unions and employing our underutilised youth? To do that we must stop our addiction to cheap unskilled foreign labour and bravely upgrade to higher value-added industries in which education reform popularises science and technology, innovation and competitiveness. To do this, we have to tap into our students’ potential by developing their critical and creative thinking faculties.

The Education Blueprint drafted by the Najib regime neglected democracy. It failed to reinstate our independence heirloom of an elected local government which involves a decentralised education system engaged with and responsive to the needs of the local community. Many have forgotten that local education authorities were part and parcel of elected local councils, as was the case before these elections were abolished in 1965. The new education minister should thus make the return of elected local government part of his to-do list.

Decentralising education can serve to make the education system more efficient as well as more democratic. Decentralising power away from the ministry of education and dispersing it to elected councils creates the conditions for better public services and a more robust society. Local councils are then responsible for the fair distribution and monitoring of funding for the different language streamed schools built according to need, rather than political preference. They are responsible for the coordination of admissions and allocation of places available at each school. They are the direct employers of all staff in schools and have a responsibility for the educational achievement of school children.

There should be a greater commitment by both the government and the Chinese and Tamil school lobbies to create such activities that promote closer integration. It would be the responsibility of local education authorities to provide state-of-the-art-facilities for the common use of schools of the different language streams in an education precinct. These should include libraries, IT centres, and stadiums, concert halls and common activities organised to include all the different school streams in a precinct.

There is a glaring contradiction in the blueprint’s commitment toward promoting unity and inclusiveness for it hardly considers the development and growth of the SRJK schools and independent schools within the national education system. Malaysian independent Chinese secondary schools are merely listed as one of the categories of private education in the country.

Considering Chinese and Tamil schools were part and parcel of the national education system at independence more than sixty years ago, there is no reason why sustaining them today, in our much more developed state, should be a problem. There is also no reason why the Malaysian education system cannot accommodate some English-language streams for those children whose mother tongue is English when we have had so much experience handling English-language education since colonial times.

The fact remains that whilst the population of the Chinese and Tamil Malaysians today has doubled since independence, their mother tongue schools have decreased in absolute numbers – from 1,350 to 1,285 Chinese schools, from 880 to 550 Tamil schools. The scandal of overcrowding in these schools makes a mockery of the lofty aspirations in the blueprint. The gross discrimination in financial allocation to the Chinese and Tamil schools (less than 5 percent of total allocation to all schools) through the years further demonstrate the lack of commitment by the government to mother tongue education of the non-Malays as a cornerstone of inclusiveness.

To meet the egalitarian goal of leaving no child behind, tertiary education needs to be totally free for the less privileged (say monthly household incomes of RM10,000 and below). To have a progressive and sustainable system, those from a more privileged background (say, household income RM20,000 or more a month) should pay full cost tuition fees. Otherwise, the middle class who dominate tertiary institutions will be subsidised by the working class. Those from households between RM10,000 and RM20,000 a month could pay on a sliding scale that is means-tested. This will better ensure equal opportunities for all with no racial discrimination in enrolment into tertiary educational institutions.

The principle of free primary and secondary education for all should extend to the 60 independent Chinese secondary schools in the country because they have been maintained all this while by the Chinese community since 1961 and their Unified Examination Certificate (UEC) is now recognised by the Harapan government.

Education has been a contentious issue in Malaysia ever since independence. If we are to progress as a truly “developed” nation, we need a thorough-going reformulation of our education system founded on egalitarian principles both in terms of opportunities and in institutional practice. A tangible educational policy must focus on nurturing all Malaysians regardless of social class or ethnicity to foster a nation of mature, critical and creative thinking individuals and that bridges the huge differential between manual and intellectual labour in Malaysian society. Above all, meritocracy must never be sacrificed in our attempts at forging an egalitarian society.

If we are not to be left behind in the Asean league of nations, we would do well to quickly introduce education reform to popularise science and technology, innovation and competitiveness so that we can upgrade to higher value-added industries in order to achieve a high-income society. To do this, we have to tap into our students’ potential by developing their critical and creative thinking faculties.

To this end, Malaysians deserve quality holistic education that encourages the learning of the arts and humanities as well as scientific and technological knowledge required for research and development and vocational skills. At the same time, education must be secular, free and fair. Let academic freedom, students’ self-government and campus autonomy be the new environment in our tertiary institutions.

KUA KIA SOONG is Suaram adviser and an education activist.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable