Upholding the spirit of racial equality and student autonomy

COMMENT | Recently, Malaysia was alarmed by the commencement of a national event that fanned the flames of controversy in the country.

The Malay Dignity Congress was jointly organised by four public universities, including the University of Malaya (UM). The vice-chancellor of UM, Abdul Rahim Hashim was one of the speakers during the congress.

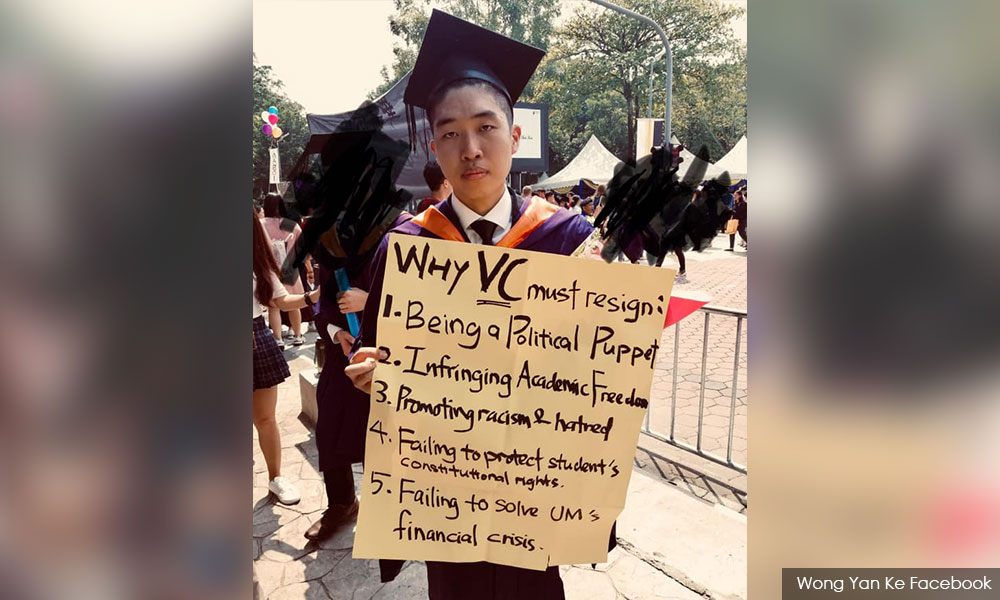

This incited student activist Wong Yan Ke to protest against the vice-chancellor during his convocation ceremony.

This matter has garnered widespread attention and the UM Law Society believes in the grave importance of imparting the legal and social viewpoints towards the issue.

Malay Dignity Congress

The University of Malaya Malay Excellence Studies Centre under the Office of the Vice-Chancellor was one of the organisers of the Malay Dignity Congress, alongside Universiti Putra Malaysia, Universiti Teknologi Mara and Universiti Pendidikan Sultan Idris.

This congress was held to unite the Malay community and to collectively defend their dignity which was deemed to be severely tarnished, as according to the Chief Executive of the Malay Dignity Secretariat, Zainal Kling.

The vice-chancellor from our very own university echoed this in his speech, and among the things he spoke about included the propagation of Malay political dominance.

The congress and its content in general, has sparked concern, especially after scrutiny of the resolutions presented in the congress which includes the abolishment of vernacular schools, a demand for scholarship percentage for the B40 and bumiputeras, a request for all top government positions to be held by Malays only, policies to safeguard the economic interest of the Malays, and an urgency for the government to take action against individuals or organisations that meddle with Islamic matters.

Home to a multicultural society, the diversity of race and religion forms what we know as Malaysia. We have progressed as a society from former times, and thus, it is only right that we unify as Malaysians despite our differences and completely eradicate any belief that any race is superior than another.

The Federal Constitution provides several provisions that uphold the value of racial equality.

Article 8(1) of the Federal Constitution expressly provides that ‘all persons are equal before the law and entitled to equal protection of the law’.

Article 8(2) further explains that except as expressly authorised by the Constitution, there shall be no discrimination against citizens on the ground only of religion, race, descent, place of birth or gender in any law or in the appointment to any office or employment under a public authority.

Besides that, Article 136 states that all persons of whatever race in the same grade in the service of the Federation shall, subject to the terms and conditions of their employment, be treated impartially.

However, Article 153(2) has always instigated discourse amongst Malaysians as this article allows the Yang di-Pertuan Agong to reserve quotas for Malays and natives of Sabah and Sarawak in respect to positions in the public service and this provision affirmed the special position of the Malays and the natives in this country.

Article 153(5) was nonetheless clarified by Article 153(2) whereby it expresses that Article 153 does not derogate from the provisions of Article 136.

Article 153 must be read together with Article 136, for us to understand that the law permits reservations and quotas upon induction, but the public servants must be treated equally once in service.

Even articles on the appointment of the prime minister, cabinet, deputy ministers, parliamentary secretaries and political secretaries are absolutely free of any race, religion, region or gender bias.

Given that, their demands such as to have only Malays fill in all top government positions defies the spirit of the constitution that provides for equality of the law.

In addition to the general agenda, we wish to highlight a few sentiments that were explicitly uttered in the speeches of the UM vice-chancellor as well as our prime minister, which we unfortunately view to be contradictory to Malaysian values of unity in diversity.

The vice-chancellor in his speech was adamant in ingraining the idea of upholding Malay dignity, especially when he said ‘Bukankah kuasa politik milik kita?’,which does not just go against the aspirations of equality laid down in the Federal Constitution but also regrettably implies that other citizens who are non-Malay should be inferior in the political landscape.

This statement sadly insinuates a supremist ideology of Malay dominance. The UM Law Society condemns any form of remarks that taints the multicultural landscape of our country and we empathise with our fellow Malaysians who have suffered from this prejudicial ideology.

Furthermore, Mahathir in his speech intended to encourage the Malays to be more economically proactive and to use their resources wisely to uplift their economic and social standpoint.

However, after listening and discerning what the prime minister had to say during the congress, our hearts are torn.

In the course of his speech, he uttered a few racially discriminatory remarks towards the non-Malays and we wish to highlight and point out a few of them which we do not agree upon.

Firstly, he referred to non-Malays as ‘orang lain’ and even stated, ‘Kalau dahulu kita boleh harap kerana kerajaan dipimpin oleh orang Melayu, memang kuat sekarang tidak kuat kerana mahu tidak mahu, kita kena ambil kira perasaan orang lain’ and ‘Kita terpaksa kongsi dengan orang lain’, which in our opinion strongly suggests two things.

The first is that non-Malay Malaysians are not of an equal standing. Secondly, is that the consideration of non-Malay interests is not of equal priority to the government.

He also stated that ‘Kita bergantung kepada orang lain untuk mendapat kemenangan, apabila kita bergantung kepada orang lain sedikit sebanyak kita terhutang budi kepada mereka’, which questions the achievements of non-Malay Malaysians.

We are of the opinion, that prominent figures such as the prime minister and the vice-chancellor, who are representatives of a multicultural society, should always carry the idea of racial equality and stand up against any form of prejudice or discrimination.

In conclusion, we refer to Article 10(1)(b) of the Federal Constitution that provides for the rights of citizens to assemble peaceably, therefore we acknowledge the rights for any person to assemble and attend such a congress.

The content that was presented is detrimental to fundamental values that enables Malaysia to function as a multicultural country and for Malaysians to be unified.

We urge our fellow Malaysians not to be desensitised to racial supremacist ideologies and to remember that this country is ours, for all Malaysians of all races and religions.

Student protests

Wong Yan Ke and Eden Kon Hua En’s actions could be seen as a form of student activism.

Wong protested on stage, whilst receiving his scroll. He had brought with him a placard with wordings such as ‘Tolak Rasis’ and ‘Undur VC’ and proclaimed ‘Ini tanah Malaysia’.

This has resulted in Wong’s transcript being withheld and his actions causing the university to lodge a formal police report, which is currently being investigated under Section 504 of the Penal Code for intentional insult with intent to provoke a breach of the peace.

Kon, however, was barred from his own convocation ceremony as it was alleged that after a security check, he was found to be in possession of a placard containing statements which the university believed were provocative and could disrupt the flow of the ceremony.

Viewing this issue from a legal perspective, it can be observed that there has always been a tight grip on student activism enshrined in the University and University Colleges Act 1971.

Section 16(1) of the said Act grants authority to the vice-chancellor in suspension or dissolution of any organisation, body or group of students of the University that conducts itself in a manner which it considers detrimental or prejudicial to the interests or well-being of the university, or to the interests or well- being of any of the students or employees of the university, or to public order, safety or security.

This is also a reflection of the Kaedah-Kaedah Universiti Malaya (Tatatertib Pelajar-Pelajar) 1999, which is a provision that all students are signatories to, also known as the Aku Janji which states that students are prohibited from acting in a manner that harms the importance, well-being and reputation of the university, the university staff and its students.

Freedom of expression is guided on certain parameters and necessities with regards to public order, morality, defamation and incitement to any offence.

Upon research of the general rules in regards to the etiquette expected of a graduate, it is not explicitly provided in any university statute nor internal policies as to the extent that students are allowed to protest. Thus, this is why we must evaluate on the premise of implied limitations as well as past precedence.

As the police are currently investigating the issue under Section 504 of the Penal Code on intentional insult with intent to provoke a breach of the peace, we seek to provide the public a legal and objective perspective on the matter.

In the 2018 case of Liau Choy Wan v PP, the court was of the opinion that public interest should be the paramount consideration in deciding the legitimacy of a protest.

The court also went to the extent of clarifying that to be charged under the said section, no actual violence nor a breach of peace is required, whereas a mere possibility was good enough to be charged under the section.

Serving as persuasive authority, we can also refer to the Indian case of Fiona Shrikhande v State of Maharashtra & Anor, whereby the Indian Supreme Court was of the opinion in para materia to Section 504 that to successfully charge one under the section, the insult must provoke the insulted individual, with the accused having knowledge that his or her insult would provoke another to break public peace.

The court was also of the opinion that background facts, circumstances, occasion of event, the manner in which they are used, the person or persons to whom they are addressed, the time and the conduct of the person who has indulged in such actions are all relevant factors to be borne in mind while examining a complaint lodged for initiating proceedings.

Therefore, we comprehend the concern of the university in regards to the view that a formal convocation ceremony may not be a suitable platform to have a legitimate protest.

However, taking into consideration the surrounding circumstances in regards to the said case, the protest had not disrupted the flow and procedure of the ceremony, had not prevented any other student from obtaining their scroll or the enjoyment of the experience of a convocation nor incited any form of violence, which is why we stand with the two students and support their right to freedom of expression.

In light of this issue, some parties petitioned to revoke Wong’s degree. However, it is important to note the circumstances in which a revocation of an academic transcript can be done.

According to Kaedah-Kaedah Universiti Malaya (Ijazah Sarjana Muda) 2019 Bahagian IX titled “Pengijazahan”, Kaedah 23(2) allows a revocation on the basis of a failure to clear academic bills while Kaedah 23(3) allows for revocation on the basis that the university is satisfied in its finding that the accused had falsified documents crucial to his or her fulfilment of the degree requirements or had committed academic dishonesty that in the university’s view is not worthy to be granted a degree.

This is in line with the University and University Colleges Act 1971 Schedule 1 Item 53, which allows the university to strip an individual off any conferred academic honour upon being found guilty of a scandalous act which according to the provision is defined as wilfully giving any officer, employee or authority of the university any information or document which is false or misleading in any material particular in obtaining a degree, diploma, certificate or other academic distinction from the university.

The individual however must be heard and be decided on a 2/3 decision by the board.

Therefore, the UM Law Society believes in the importance of freedom of expression as a fundamental liberty that in this context, enables a students’ right to academic freedom and with that we stand with Wong and Kon who exercised their right and were wrongfully reprimanded by the university authority.

We hope the university administration does right by granting them their academic transcripts.

We urge the government that believes in student autonomy and activism to critically review the University and University Colleges Act 1971 that focuses much on students’ ability to participate in politics.

It is high time that our laws promote a holistic approach on the higher education, focusing on the rights of students and the authorities of the board, senate, and vice-chancellor to be properly laid out.

This is to ensure a check and balance, and to promote an environment for students to exercise their constitutional rights maturely.

We extremely regret the circumstances that has plagued the national scene and we plead for all parties to take high regard of the spirit of racial equality and student autonomy.

THE UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA LAW SOCIETY can be contacted at [email protected].

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable