Buying a big stick: South Korea's military spending has North Korea worried

South Korea and North Korea have continued to pour resources into modernising their militaries despite a frenzy of diplomacy since 2018, data shows, creating a point of tension that has sharpened as talks have stalled.

Military buildups on both sides of the heavily fortified border between the two nations have come to the forefront with recent short-range missile launches by North Korea, perfecting an arsenal it says is necessary to defend against new South Korean weapons.

On Wednesday North Korean state media reported that leader Kim Jong Un had personally supervised on Tuesday the test-firing of a large multiple-rocket launch system, a type of weapon analysts say threatens forces in South Korea.

Pyongyang has sharply criticised US-South Korean military drills and South Korea’s defence procurements - including an aircraft carrier, stealth fighters and spy satellites - as undisguised preparations for a preemptive strike.

In a commentary on Friday, North Korean state news agency KCNA said South Korea’s pursuit of new weapons systems is an “unpardonable act of perfidy” that threatens to undermine peace on the peninsula.

South Korea’s Ministry of National Defence (MND) did not respond to requests for comment.

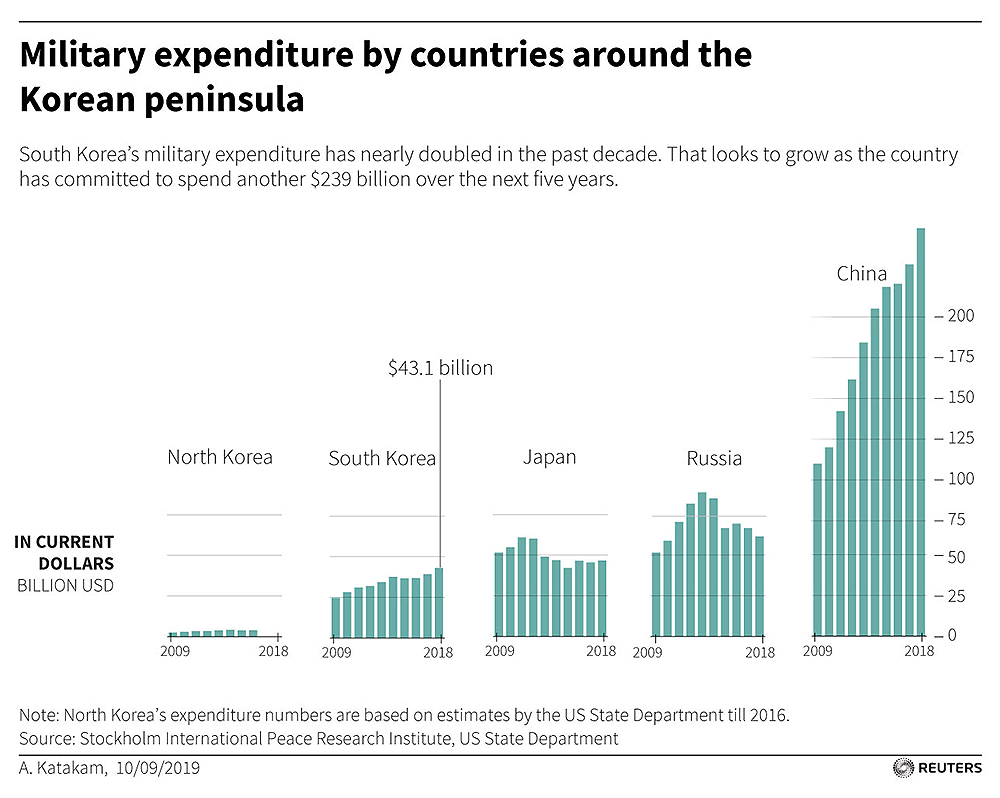

South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s administration has committed billions of additional dollars to the country’s defence budget, which is already among the largest in the world.

In 2018 South Korea’s military expenditures reached US$43.1 billion, an increase of seven percent compared with 2017, according to the MND. It was the biggest single-year jump since a 8.7 percent increase in 2009.

In July the MND announced South Korea would build a light aircraft carrier, the country’s first. And in August it unveiled a plan to spend about US$239 billion more between 2020 and 2024.

About US$85 billion of the future budget is earmarked for arms improvements, representing an average 10.3 percent year-on-year increase.

“Given the recent uncertain security environment, the government is investing heavily in strengthening its defence capabilities,” the MND said when the plan was announced.

By 2023, the “force enhancement” budget will account for more than 36 percent of total defence spending, up from about 31 percent this year, according to South Korea’s 2018 Defense White Paper.

The planned aircraft carrier is expected to accommodate vertical-landing F-35B stealth fighter jets.

Among the other weapons on Seoul’s shopping list are new missile defence systems; three more destroyers equipped with the cutting-edge Aegis radar system; spy satellites and high-altitude reconnaissance drones; anti-submarine helicopters; maritime patrol aircraft; submarines capable of firing cruise and ballistic missiles; and a warship armed with guided missiles.

“Neither Korea wants to a full-blown confrontation, but both want to make sure they have the weapons platforms and defence resources available in the event a flare-up happens,” said Daniel DePetris, a fellow at Defense Priorities, a Washington-based think tank.

Expensive arms race

Of most immediate concern to North Korea, this year South Korea took delivery of the first of 40 land-based F-35A stealth aircraft from the United States.

North Korea criticised that as well as other weapons announcements as a reckless arms build-up that was forcing it to develop new short-range ballistic missiles (SRBMs) to “completely destroy” the new threats.

The F-35 “puts North Korea’s anti-aircraft and anti-missile defence systems in an extremely vulnerable position, which is likely why the North is responding by accelerating its own SRBM development,” DePetris said.

North Korea also views the F-35s as violations of a military de-escalation agreement the two countries signed in September 2018. The Koreas agreed to cease “all hostile acts,” but the deal did not mention new weapons.

With North Korea under tight international sanctions, the North cannot afford an arms race, analysts said.

In 2016, the last year for which estimates were available, North Korea spent an estimated US$4 billion, or 23 percent of its GDP, on defence. Almost five percent of the population serves on active duty in the military, according to the US State Department’s 2018 World Military Expenditures and Arms Transfers report.

Although Kim has signalled interest in using more of the country’s vast defence industry to work on civilian projects, there is little sign of progress, and international aid organisations say tens of thousands of North Koreans face food shortages.

Changing military situation

While the surge in military spending may seem to contradict Moon’s push to engage North Korea, analysts say it is largely driven by other issues, including South Korea’s changing demographics and the country’s relationship with longtime ally the United States.

Since the 1950-1953 Korean War, the American military has retained the authority to control hundreds of thousands of South Korean forces alongside the roughly 28,500 US troops in South Korea if another war breaks out.

Moon has made obtaining “operational control,” or Opcon, of those joint forces a major goal of his administration, and building up the military is an important part of gaining US approval for that, said Kathryn Botto, an analyst at the Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Additionally, South Korea’s population is ageing, reducing the number of young people available to serve in South Korea’s military.

By 2025, South Korea plans to reduce its standing military from 599,000 troops to 500,000, according to the Defense White Paper, with the aim of “a military that is smaller in size but stronger in combat.”

The Trump administration has pushed South Korea to buy more American weapons and paying more for US troops stationed there, Botto said.

“Investing more in capabilities that it can acquire from the US both helps keep Trump on Moon’s side and augments his Opcon transfer and defence reform goals,” she said.

But analysts also say that South Korea wants to reduce its dependence on American gear, partly because it is frustrated by Washington’s occasional unwillingness to share the best technology.

“In order to secure self-defence capabilities and lead the development of national science and technology, the acquisition policy will change to centre around domestic R&D rather than overseas purchases,” the MND said in its August budget announcement.

Moon wants to build up the military’s ability to operate as independently as possible before the stagnating economy makes such spending harder, said one Western military official in Seoul, who was not authorised to speak to the media.

“South Korea is on course to be the largest military R&D spender in the world, as a proportion of its budget. They are angling to be a bigger player than ever on the world stage.”

- Reuters

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable