How the story of 15 Bateq villagers dying in Gua Musang unfolded

KINIGUIDE | The deaths of 15 Orang Asli villagers in the Bateq community of Kampung Kuala Koh in Gua Musang, since early May have decimated a once-thriving rural paradise.

The human tragedy exposed shortcomings in the administration of emergency medical treatment, and raised questions about whether the destruction of the community's habitat or possible contamination of its water supply were behind the deaths.

News of a number of deaths, estimated to be around eight to 10 within a

month, first surfaced on June 2 when Sahabat Jariah, an NGO working with the

Orang Asli, made a Facebook post highlighting that a number of villagers had

died of a mysterious disease.

Another NGO, Klima Action Malaysia, then announced a donation drive, saying it was planning to drop off food, water and medical supplies to the stricken village.

Village cordoned off

On June 9, news broke out nationally when Minister in the Prime Minister's Department P Waythamoorthy flew to Gua Musang. His aide confirmed that there had been 14 deaths in the village since early May.

The village was soon cordoned off to outsiders and declared a red zone. Kelantan Health director Dr Zaini Hussin said the move was to curtail the spread of pneumonia infections that could be transmitted through respiration.

The Health Ministry announced that it was carrying out tests to determine the cause of infection. Initial tests ruled out leptospirosis and tuberculosis, according to minister Dzulkefly Ahmad (photo).

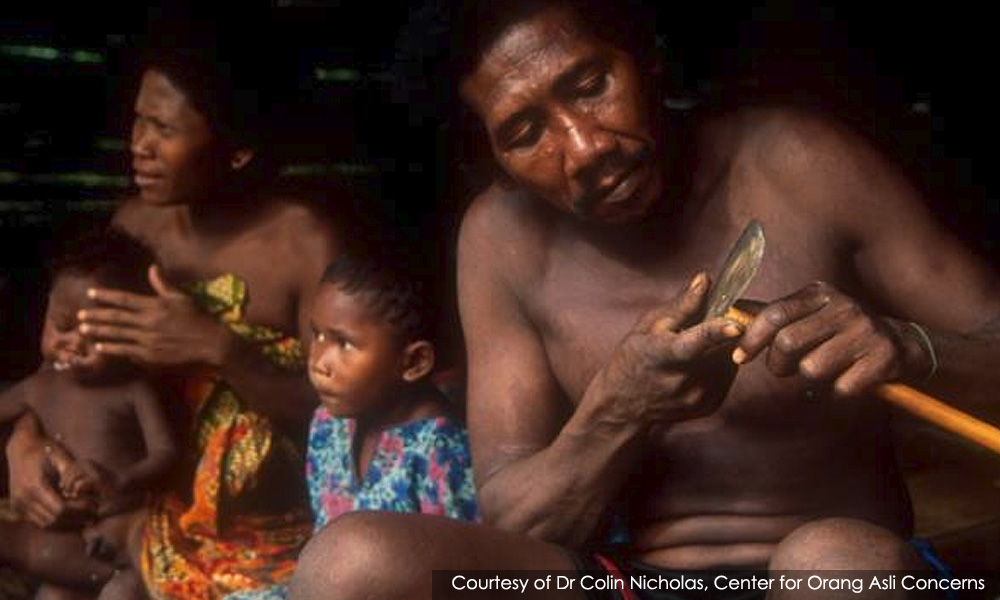

Colin Nicholas, executive director of the Centre for Orang Asli Concerns, told Malaysiakini that the root of the problem was that the natural habit of the Bateq was being destroyed.

"The problem is not medical, but a direct result of what happens when people’s rights to their customary lands are not recognised and that land is destroyed.

"Just seven to 10 years ago, if you visited them, they were perfectly healthy and psychologically happy.

"But their land has been taken away, in this case by the Kelantan government. And their resource base has been destroyed," he said.

Nicholas' views were echoed by an outreach doctor, Dr Steven Chow, who had visited the community on April 28, just a week before the deaths.

"This is a community left behind, dying from neglect," he said.

"After their land was taken away for plantations, these people were essentially left to fend on their own and were virtually cut off from the resources of the jungle which they had previously depended on for their survival."

Traditional burial practice

Initial postmortems indicated that two Bateq villagers had died of pneumonia, but an order was given for their bodies to be exhumed.

Twelve more bodies had to be retrieved as they had been laid to rest according to traditional beliefs.

The traditional burial practice of the Bateq is for the corpse to be wrapped in tree bark and carried across a river, which according to their belief system, prevents the spirit from returning to the village.

The body is then harnessed to a tall tree in the burial area using vines, and is left there to decompose. Burial grounds are considered taboo by the Bateq.

On June 14, Deputy Prime Minister Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail confirmed the Environment Department's findings that there was no water contamination from manganese mining at Aring 10, located three kilometres from Kampung Kuala Koh.

An interview with Som Ngai (photo), 50, who lost her husband, Hamdan Keladi, and three children in the space of two weeks, brought home the severity of the tragedy.

"I am still so sad, imagining the pain and suffering of my husband and children.

"I cannot do anything, even cooking and cleaning. I was so sorry to see their condition. Just lying and unable to eat or drink," she added.

A toddler became the 15th victim

On June 16, it was reported that more than 150 Orang Asli from the Semaq Beri tribe had left their homes in Sungai Berua, because of an influx of Bateq villagers who had fled Kampung Kuala Koh over the past two weeks.

The same day, Bateq toddler Nasri Rosli became the 15th victim to die, passing away due to measles in a hospital in Kota Bharu.

The Health Ministry also identified measles as the disease affecting the Bateq community.

As many as 37 of 112 members of the community, who are reported to be suffering respiratory tract infections, have contracted measles, Dzulkefly said.

He said these cases were confirmed by laboratory tests, while the results for other diseases like tuberculosis, melioidosis, leptospirosis and coronavirus infections were negative.

Efforts to confirm the cause of the other deaths are still ongoing.

Reacting to the revelation, Chow said that an outbreak of measles is a plausible explanation for the deaths, but attempts to link the community’s way of life with the tragedy are unfair.

He dismissed the idea that the villagers were not keen to be vaccinated, and rejected claims that the nomadic lifestyle and burial practices of the Bateq might have played a role in the deaths.

Former health minister Dr S Subramaniam said the possibility of deaths from measles reflected the inability of the Orang Asli to "defend themselves against such illness due to malnutrition, and probably poor immune defence."

He lamented that citizens were falling victim to easily treatable diseases in this day and age.

Autopsies completed

On June 19, Kelantan police chief Hasanuddin Hassan announced that the autopsies on the remains of all the Bateq villagers had been completed.

The same day, Waythamoorthy denied Deputy Kelantan Menteri Besar Mohd Amar Nik Abdullah's claim that the government plans to relocate the community away from Kampung Kuala Koh.

On June 20, Dzulkefly confirmed that a second postmortem conducted on the two deceased Bateq villagers initially deemed to have died of pneumonia, revealed that they died of measles instead.

When asked why the first postmortem on the first two victims had not detected measles, given that the resulting rashes should be visible, he answered that it was because the skin of the tribespeople was too dark.

On June 22, Dzulkefly said that there have been three new cases of measles reported, bringing to 116, the total number of confirmed measles cases in the village since June 3.

Jakoa DG expresses frustrations

On June 29, Orang Asli Development Department (Jakoa) director-general Juli Edo told a forum that when he visited the stricken Bateq village, "there was clearly a divide, a 'them and us' situation, and the relationship between the government service providers and the villagers was not warm."

He went on to admit that "the majority" of Jakoa staff were "not passionate" about their work, and were there just to "makan gaji" (earn a salary). He also lamented the "ethnocentric attitude" of the staff.

Juli (photo) went further in an exclusive interview with Malaysiakini on July 5, saying that more deaths could be expected if the poverty of the Orang Asli was not addressed.

“The Orang Asli community is still mired in poverty, with nearly 99 percent of them belonging to the B40 income group and most of them in the hardcore poor category.

“What happened in Kuala Koh is a lesson to all. However, I am satisfied with the immediate action taken by the Health Ministry and other government agencies to combat the disease, rather than let it spread to other areas.

“In my opinion, in order to prevent this tragedy from recurring, the first step is the government must strive to alleviate the Orang Asli community from poverty.

PM's dept on Bateq community

On the same day in Parliament, the Prime Minister's Department painted a bleak picture of the state of the Bateq tribe.

In a parliamentary written reply, it said Jakoa has no record of any high-achieving students, university graduates or civil servants from the community.

"Overall, the educational achievement of the Bateq tribe between 1998 and 2018 is poor, with a high illiteracy rate.

"According to Jakoa's records, there is no high-achieving student in primary and secondary school, no university graduate and no one works as a civil servant," it said.

It said based on a 2010 census, the Bateq numbered 1,447 people.

Cause of death for three confirmed

On July 6, the Health Ministry said that laboratory testing of the three of the deaths among the Orang Asli at Kampung Kuala Koh confirmed that the cause of death was complications due to measles.

However, the postmortems carried out on the other 12 bodies found by the police could not determine the cause of death, largely due to decomposition and contamination.

These 12 bodies were originally buried according to traditional Bateq rites.

Deputy Health Minister Dr Lee Boon Chye said on July 8, that authorities are facing a tough challenge in determining the cause of death of the 12 as little remained of their bodies.

Denying that the delay of the postmortem report was due to government inefficiency, he nevertheless admitted that more could have been done if the bodies had been discovered “much earlier.”

A day later, Gua Musang police chief Mohd Taufik Maidin said the district disaster committee had decided to lift the red zone restriction effective from 8am, July 8, after the area was confirmed to be safe from any infectious diseases.

He said the Health Ministry, through the Gua Musang District Health office, had informed that it was satisfied with the health situation in the village, which has now returned to normal.

Another measles death in Terengganu

On July 8, an Orang Asli woman died due to measles in Terengganu, bringing the number of confirmed deaths due to the measles outbreak along the state’s border with Kelantan to four so far.

Dzulkefly said the 39-year-old victim, who was confirmed to have come down with measles through laboratory tests, died at the Sultanah Nur Zahirah Hospital in Kuala Terengganu.

He said that since the measles outbreak was reported on June 3, cumulative cases numbered 178, with 147 in Kelantan with three fatalities, Terengganu (23 cases, one fatality) and Pahang (eight cases, no fatalities).

Those statistics did not account for the 12 Bateq villagers for whom the cause of death could not be confirmed.

Still under quarantine

In Parliament's Question Time on July 16, Deputy Prime Minister Dr Wan Azizah Wan Ismail hailed the involvement of the National Disaster Management Agency (Nadma), saying that it had helped formulate a more effective disaster management strategy and action plan.

She said the Kuala Koh health crisis was classified as Disaster Level One, and was managed in line with disaster management culture – encompassing preparedness, response and rehabilitation and mitigation to reduce its impact.

“Nadma will also carry out a postmortem for the incident to study and identify the room for improvement in the management of future disasters,” she said.

Also on July 16, Gua Musang social welfare officer Hizani Ibrahim said that 168 Bateq villagers, already discharged from hospital, were being quarantined at the temporary relief centre (PPS) at Taman Etnobotani, Gua Musang.

They would be allowed to return home once they have fully recovered, he said.

Kelantan/Terengganu Jakoa director Hashim Alang Abdul Hamid also announced that 300 people were taking part in a gotong-royong programme on July 17, to help clean up the village to prevent a recurrence of measles.

He said the decision to hold the gotong-royong was reached by 11 entities including NGOs.

Independent reports cast fresh doubts

Fresh doubts as to the underlying cause of the deaths erupted on July 18 when laboratory tests on samples taken from the waters sourced around Kampung Kuala Koh revealed contamination and toxic substances.

Chow, who is also the Federation of Private Medical Practitioners' Associations Malaysia (FPMPAM) president, said the samples were taken on June 10 and 11 from five sources.

FPMPAM, along with Pertubuhan Pelindung Khazanah Alam Malaysia (Peka) and the Centre for Malaysian Indigenous Studies, sent the samples for testing in three independent laboratories.

The testing was carried out by the Environmental Engineering Laboratory at Universiti Malaya's Faculty of Engineering, ALS Life Sciences and the Kuala Lumpur branch of ChemLab.

These test results revealed that samples from Sungai Pertang – the main source of water for the community – were not suitable for human consumption unless extensively treated. The water is not even suitable for recreational use.

The Environmental Engineering Laboratory found high levels of ammoniacal nitrogen, ranging from 11.2mg/L to 25.2mg/L. Acceptable levels for river water do not exceed 0.9mg/L.

One study also found that the level of manganese in the water was 2.53mg/L – more than 12 times the safety standard of 0.2mg/L set by the Health Ministry.

The studies also found an unacceptable level of faecal contamination in the water.

The groups sought a meeting with the health minister to urge him to set up an inquiry into the villagers' deaths. They met in Putrajaya on July 18.

This instalment of KiniGuide is compiled by MARTIN VENGADESAN.

The guide was first published on June 22, 2019. It was further updated on July 8 and 22.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable