LETTER | Dr M should blame himself for disunity among Malays

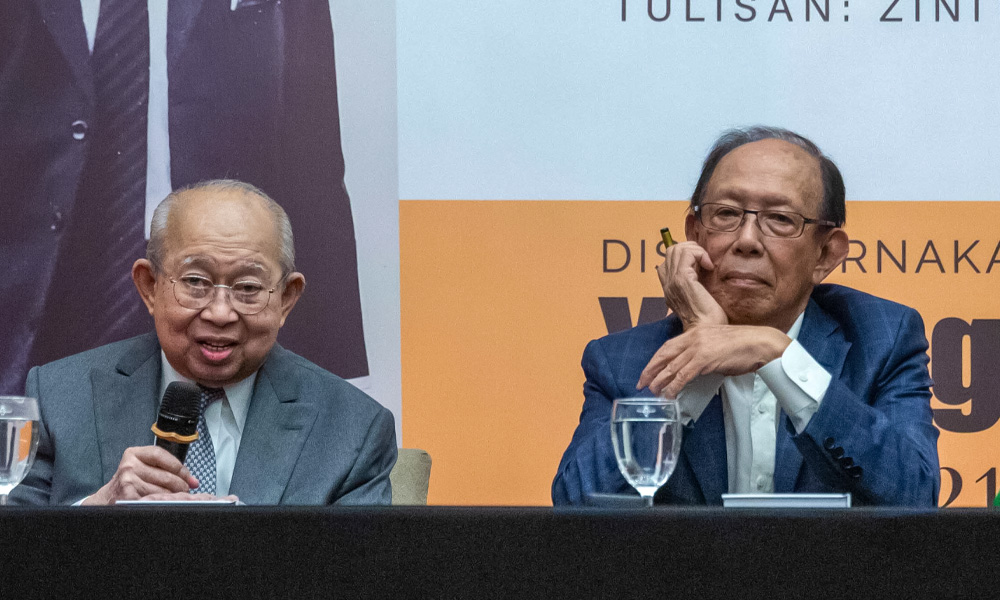

LETTER | Former prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad recently expressed concerns about the division among the Malays.

According to him, the unity of the Malay community weakened under the leadership of his successors.

During his 22-year tenure, the Malays largely supported Umno. However, after his resignation in 2003, when he handed over power to Abdullah Ahmad Badawi, Umno faced challenges and lost control of five states in the 2008 general election.

Yet it is important to recognise that the root of these issues lies with Mahathir himself. Mahathir rose to power under favourable conditions.

Malaysia’s economy had been growing robustly for decades, thanks to the prudent economic management of a highly competent bureaucracy. Governance and tax collection were efficient and debts were minimal. Natural resource wealth, including oil, was managed professionally.

A decade of robust redistribution to the country’s ethnic Malay majority had restored social stability after the race riots of 1969.

Foreign investment was abundant and set to increase even further. Mahathir inherited one of the most cohesive ruling parties - Umno and the BN coalition.

The regime was authoritarian but not excessively repressive or disliked in comparative terms. In short, Mahathir held a strong position when he became prime minister in 1981.

Privatisation was part of his growth strategy but the beneficiaries were businesspersons loyal to him rather than talented entrepreneurs.

Umno split in 1980s

When the global economy entered a recession in the mid-1980s, patronage began to dwindle. Umno split, largely due to Mahathir’s heavy-handed style of governance.

Mahathir’s two most talented rivals, Tengku Razaleigh and Musa Hitam, left Umno despite their deep personal ties to the party, mainly to distance themselves from Mahathir.

In response, Mahathir launched a police operation under the pretext of racial tensions, imprisoning and intimidating political opponents, and solidifying his autocratic control.

So much for unifying the Malay polity.

By the late 1980s, all the defining features of Malaysia’s current crisis under former prime minister Najib Abdul Razak’s leadership were already evident under Mahathir.

The regime was becoming more repressive. The office of prime minister was turning into a bastion of autocracy. Ethnic tensions were being exploited for political gain, especially after severe election losses at the hands of the opposition. The economy was becoming a worry

Mahathir’s vision for Malaysia included turning it into a developed country by 2020. His Vision 2020 plan aimed at creating a united Malaysian nation, fostering a mature and tolerant society and ensuring equitable wealth distribution.

Unfortunately, the current narrative from the 99-year-old politician diverges from this vision. Instead of promoting unity, he has engaged in divisive politics, even working with religious extremists to topple the present government.

His recent actions have put the country in a negative light and hindered progress toward a truly multiracial Malaysia.

Return to power, abrupt departure

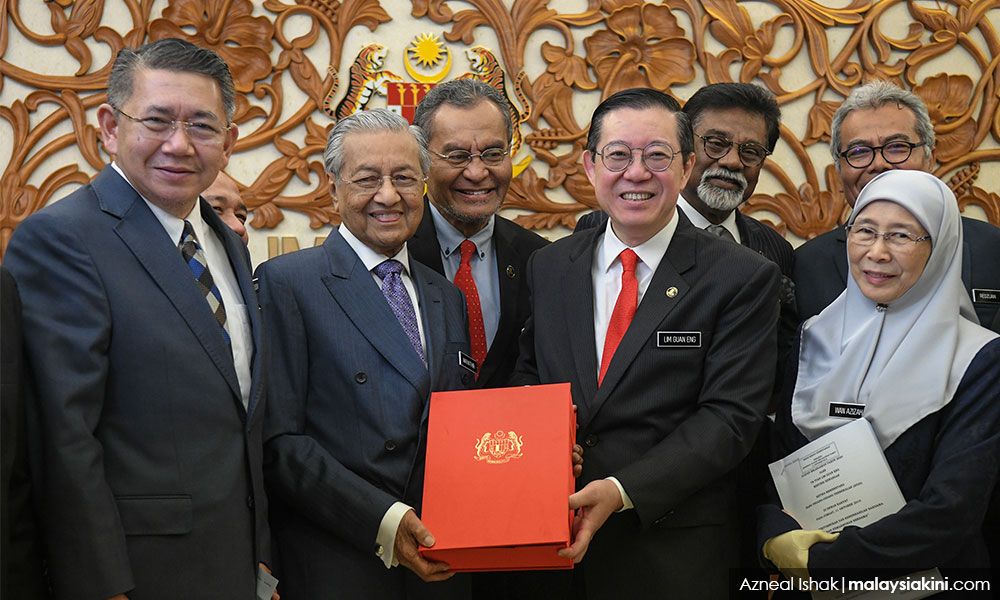

In 2018, Mahathir returned to power after Pakatan Harapan ended the 60-year of Alliance/BN reign.

Interestingly, he defended the DAP even before assuming office for the second time. In a statement from September 2016, he acknowledged that he had been “wrong about the party,” emphasising DAP’s multiracial character and its use of the national language in its activities.

However, the political landscape shifted dramatically. Mahathir’s resignation in 2020 led to the collapse of the Harapan government.

While he now blames DAP entirely for this outcome, it’s essential to recognise that no one from Haraapan attempted to oust him. Instead, he chose to resign, a decision consistently maintained by Bersatu president Muhyiddin Yassin.

Ironically, Mahathir now is trying his hardest reportedly seeking a political pact to “save the Malays”.

Despite previous vows never to work with those who “stabbed him in the back”, he finds himself in the same boat as the same political enemies that tormented him in his first tenure as prime minister.

Beyond these political manoeuvres, the discourse in Malaysia remains fixated on the past. Distorted interpretations of history dominate discussions, exemplified by Mahathir’s recent claim that promoting Malaysia as a multiracial country is unconstitutional.

The narrative often portrays Malays as under siege, with non-Malays held responsible.

Yet, the reality is more nuanced. Malaysia’s demographics reveal that bumiputra (Malays and indigenous groups) constitute nearly 70 percent of the population, while the Chinese and Indians make up smaller percentages.

Non-Malays have long accepted the country’s racial equation, living with the political realities shaped by this diversity.

As we move forward, it’s crucial to shift our focus. Rather than dwelling on the past, Malaysians must envision an economically strong, progressive and united future.

Mahathir’s Vision 2020-a vision for Malaysia - remains relevant. Regardless of race, the talent and resourcefulness of all Malaysians are essential to achieving this vision.

Our competition lies beyond our borders, not within them.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable