LETTER | Say no to a 'sue-happy' society!

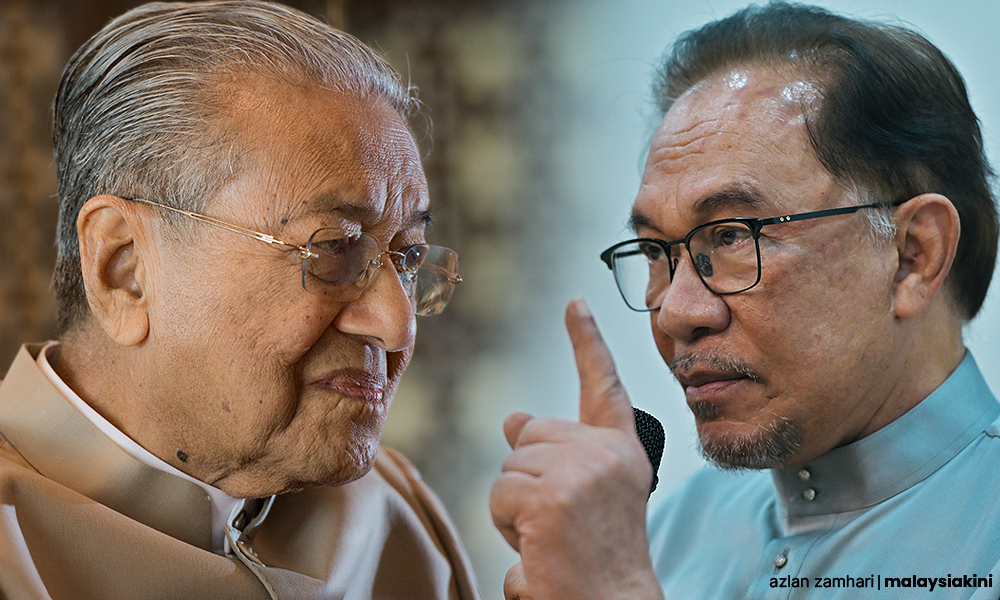

LETTER | On this year's World Press Freedom Day (May 3), Mahathir Mohamad, who, during his tenure as prime minister, made it to the annual list of “10 Worst Enemies of the Press” by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) for three consecutive years (1999, 2000 and 2001), has filed an RM150 million lawsuit against Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim over claims that he had amassed wealth for personal riches while in power.

However, we need not sympathise with Anwar. Firstly, he is the incumbent prime minister and has an advantage over Mahathir. Secondly, he has been suing four political opponents in the first four months he came into office, including Perak PAS chairperson Razman Zakaria, Kedah Menteri Besar Muhammad Sanusi Md Nor, Bersatu president Muhyiddin Yassin, and PAS MP for Pendang Awang Hashim.

After Pakatan Harapan formed the government in the general election of 2018, some Harapan politicians were not reluctant to file lawsuits against their political opponents. From October to December of the same year, DAP veteran MP Lim Kit Siang, the then-primary industries minister Teresa Kok, and the then-deputy defence minister Liew Chin Tong, respectively filed or prepared to file defamation lawsuits against critics.

Kok and Liew demanded RM30 million and RM20 million in damages respectively from the same defendant, Pertubuhan Jaringan Melayu Malaysia (JMM) president Azwandin Hamzah.

I had criticised the legal actions brought by the trio, pointing out that they were members of the ruling coalition and had various channels and resources to counter criticism. Moreover, most, if not all, media outlets reported on their responses, which were sufficient to refute any unfounded accusations.

They did not suffer substantial harm and should have avoided filing mega lawsuits. In Malaysia's political reality, ruling elites filing defamation lawsuits against their political opponents put both parties in a structurally unequal position. Such action will inevitably create a chilling effect, and its impact on civil society will be greater than on the political arena.

To understand these issues, it is essential to recall the trend of “mega defamation lawsuits” during Mahathir’s first premiership.

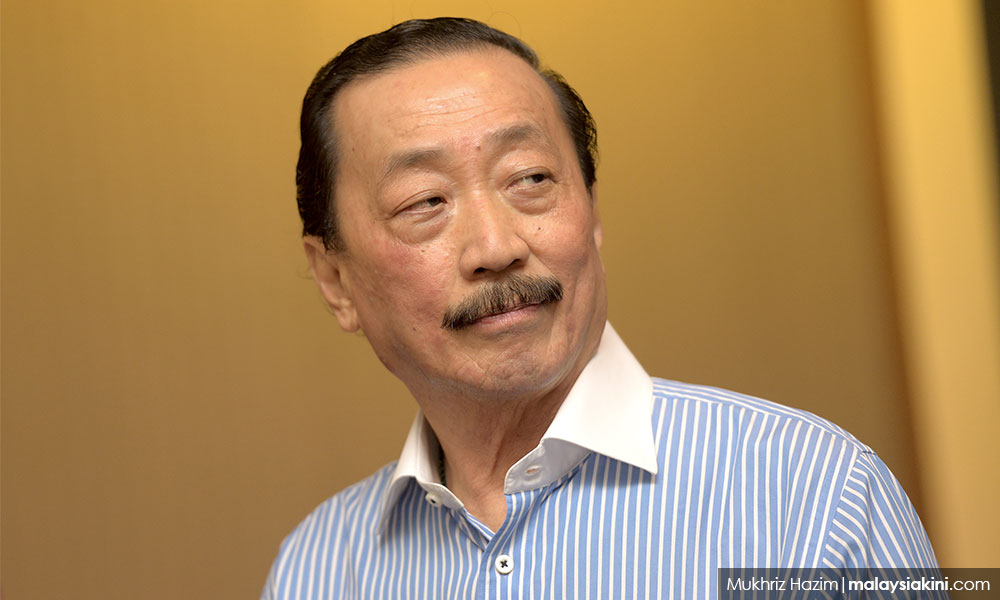

In 1992, Vincent Tan, a tycoon who allegedly has a close relationship with Mahathir, sued the owner, printer, editor, and writer of the Malaysian Industry for defamation, claiming RM20 million in damages. The High Court ruled that the seven defendants pay a total of RM10 million in damages, setting a record for the highest amount of defamation damages in Malaysian history.

Subsequently, the tycoon, through his lawyer, VK Lingam, who later became the key figure in the infamous “Lingam Tape” scandal, filed a series of mega lawsuits targeting critics including veteran lawyer Param Cumaraswamy (the then United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers), veteran lawyer Tommy Thomas (attorney-general appointed by the Harapan government in 2018), prominent economics professor Jomo KS (a member of Council of Eminent Persons of the Harapan government in 2018), The Asian Wall Street Journal as well as local newspapers.

Defamation lawsuits have become prevalent in Malaysia from the 1990s until the early 2000s, with over 88 cases claiming a total of RM7.2 billion in damages.

The Malaysian Bar Council published a report of the Bar Council on the 'Effect of defamation laws on free speech' in 2001, pointing out that Malaysia had the highest defamation damages in the Commonwealth and even possibly in the world. In the same year, the then-chief justice of the Federal Court, Mohamed Dzaiddin Haji Abdullah, stated that the defamation claims were too high and that judges should review and limit the amount of damages awarded.

The trend of “mega defamation lawsuits” eased after the Court of Appeal reduced the damages for a defamation case four months later.

A friend of mine, who is a political scientist, disagreed with my criticism of the Harapan ruling elites who were filing defamation lawsuits. He defended the Harapan ruling elites with two arguments: the filed defamation lawsuits were acceptable in view of their being civil proceedings and not criminal defamation charges, and unfounded statements may endanger the personal safety of the Harapan ruling elites.

These two arguments failed to convince me. Although in civil proceedings, the defendant does not bear the risk of imprisonment even if they lose the case, the legal expenses and damages would be a heavy burden unless the defendant is wealthy.

Following a defamation lawsuit, Lim Lip Eng, DAP MP for Kepong who is also a practising lawyer, needed to appeal to the public for donations to pay the RM2 million in damages.

In addition, defamation lawsuits are time-consuming and mentally burdensome for the defendant. The absence of the risk of imprisonment does not mean it causes no fear.

The experiences of these people will have a chilling effect on others, especially those without political backing and connections.

As for concerns about personal safety, it is likely an exaggeration. One may argue that unfounded statements can cause significant harm due to the rapid spread of the Internet and social media.

However, the Internet and social media could also enable the “defamed” ruling elites to clarify their position in the first instance. Various media outlets will also reproduce responses made by the powers that be.

Using the possibility of endangering personal safety as a defence for the defamation lawsuits of the ruling elites is a mentality similar to that of the “preventive detention” of the Internal Security Act 1960 (ISA 1960) and the Security Offences (Special Measures) Act 2012 (Sosma 2012). This approach presumes the possibility of danger and detains individuals as a precautionary measure regardless of the absence of any “clear and present danger”.

If the argument of endangering personal safety can stand, then the preventive detention made against oppositionists and dissenters by Mahathir and the government on grounds such as “threatening national security” under the ISA 1960 would all be politically correct.

In the same sense, other enforcement actions that violate democratic and rule of law principles, such as arrests, investigations and prosecutions under the Sedition Act 1948, would be deemed acceptable too.

Malaysians expect a change of government for political reforms. Now, we should seriously consider whether we want to see a resurgence of the trend of defamation lawsuits and live in a “sue-happy” society.

CHANG TECK PENG, a journalist-turned-academic, leads the Master of Arts in Communication programme at the Tunku Abdul Rahman University of Management and Technology.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable