Making education great again

LETTER | It has been over 15 months since Pakatan Harapan (won the 14th general election. In that spell of time, policies that have emerged from the Ministry of Education, such as “black shoes,” “the use of hotel swimming pools,” and khat, do nothing to raise the quality and standard of education in Malaysia. The Ministry of Education has clearly wasted 15 months of precious time but it is not too late to do something concrete and yet simple to get the ball rolling in the right direction.

The need to foster a quality education system in Malaysia can hardly be overemphasised. After almost a half-century since the New Economic Policy (NEP) and public educational spending as a proportion of GDP that is among the highest in the world, Malaysian students as a whole still lag behind students in many other countries, especially in countries that Malaysia seeks to compete with such as China, Japan, Singapore, S Korea, Taiwan and even Vietnam. Each time Malaysia has participated in the Programme for Internal Student Assessment (Pisa), and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timss) our students have done no better than falling just above or well below the fiftieth percentile among participating countries.

The problem does not lie with Malaysia’s youth but with a failure in leadership and the preference to play political football with education than to educate our children for their future. The main handicap Malaysian youths face lies in the state of the educational system they are compelled to learn in.

To foster a quality education system calls, first and foremost, for a clear definition of what quality education is. Without a clear definition and well-defined standards it would be impossible to develop the right kind of information with which to chart our progress. A broader definition of quality education would deal with critical aspects such as the ability to learn, the content of the curriculum and materials offered, processes employed in the design and delivery of programmes (especially teaching and learning methods), and the environment in which learning takes place.

An even broader definition would take into consideration the challenges that we are confronted with in the global information economy that would include the ability of school leavers to make successful school-to-work transitions and compete successfully in the global marketplace. There is clearly an urgent need to define what quality education means in the Malaysian context. The Harapan government has little time to waste on the frivolous and that includes free breakfast for all primary school students when it should be focusing on students in need.

As an immediate measure that is easily implemented because all stakeholders (students, parents, and even Harapan itself) would benefit from better schools and quality education for all our children, we can start the ball rolling by implementing a system of school report cards. School report cards are similar to the report cards that are handed out to students after each examination as a record of where they stand academically. The principal difference is that the unit of concern here is the school, and the report cards are made readily available to the communities in which the schools are located; i.e., to parents, teachers and the students. School report cards promote transparency and accountability.

They serve three main purposes: a) provide a useful and easily understood management tool (especially at the school level); b) stimulate parental and citizen involvement and demand for better school performance, thereby strengthening accountability upwards to managers of educational systems; and c) motivate education reform at all levels – school, community, region and nation.

When implemented well, school report cards have the potential to accomplish these goals. In countries where they have been implemented, they have contributed significantly to improvements in student learning and achievement. Examples abound not only in developed economies such as Canada, New Zealand and the US but also in developing countries such as Brazil, Colombia, Ghana and Kenya.

To reduce the gestation period, the content of school report cards can be confined to readily available information such as test scores in key subjects at public examinations; student flows in terms of the proportions promoted, retained and dropped out, school and teacher characteristics; student socioeconomic characteristics, and even indicators of parental and community involvement compared to the average for schools in the district, state and country as a whole.

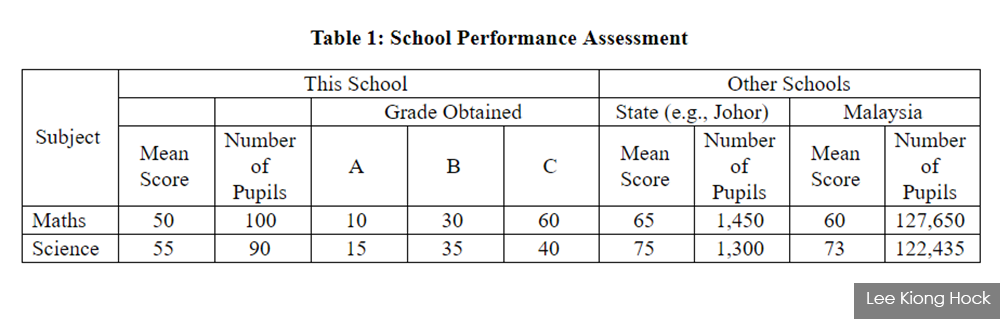

Over time, changes can be made to the amount and quality of information reported as we refine our definition of quality education. A simple school report card might look something like the following:

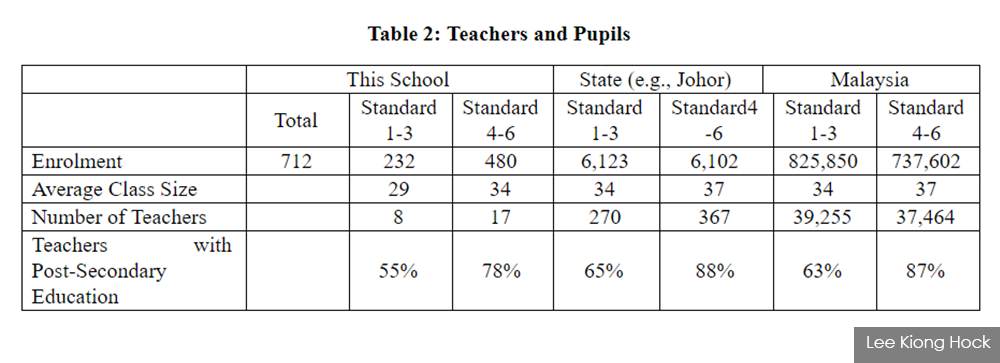

Parents (and even students) looking at a school report card such as that shown in Table 1 will readily see that the school that their children are fairing below the average in the state and country as a whole. Looking at Table 2, they can see, for instance, that the problem does not lie in the shortage of teachers for their average class size is better than that at the state and national levels. The problem may, on the other hand, lie primarily in the quality of the teachers they have; at least as measured by the proportion with post-secondary education.

Parents can then work together with the principal to demand better-qualified teachers or press for further training for the teachers in the school. Aside from parent, the Ministry of Education also benefits from having greater parental (and student) involvement in identifying weaknesses and strengths that each school possesses.

Opponents of the use of school report cards often argue that students will spend time learning the material that is tested and schools will align teaching to the material that is tested. This is, however, something that our schools already do so the introduction of schools report cards is not damaging. On the contrary, as the curricula change to meet the aims of a clearly defined quality education system, the use of school report cards will encourage students to study harder and schools to teach the new curricula which are precisely the intentions of a good school report card system.

A second common objection is that a good school report cards system is expensive. Again, on the contrary, the costs are low and the main barrier to a good school report cards system is not expense but the support and interest of policy-makers, education officials and the public as a whole. All these objections, however, pale in comparison to the benefits that Malaysia’s children will derive from having a high quality education.

It’s time to for the Harapan government to leave behind frivolous black- shoes, hotel-swimming pools and khat policies and move on to policies built around quality education, transparency and accountability

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable