COMMENT | Beware of over-censorship of social media giants

COMMENT | The Malaysian government made internet access available to the public in 1994, ahead of other Southeast Asian countries.

However, the popularisation and rapid growth of internet users only took off in 1998, an unintended consequence of then-prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad’s decision to sack the then-deputy prime minister and finance minister Anwar Ibrahim.

This political incident sparked the Reformasi movement, which led people to sign up for internet services, create email accounts, and search for Reformasi-related information online, even launching anonymous websites.

Garry Rodan (2004), an Australian academic, noted that over 50 Reformasi websites sprang up within months of Anwar’s dismissal. These websites continued to proliferate, and according to Malaysian academic Tan Lee Ooi (2010), by Aug 31, 2003, even though the Reformasi movement had waned, there were still 191 such websites. Considering the early stage of internet development in Malaysia at the time, this number is remarkable.

The Reformasi movement in 1998 and the subsequent blossoming of Malaysia’s news portals significantly contributed to the “political tsunami" of 2008 and the first regime change in 2018.

If we recognise that the two decades of political changes from 1998 to 2018 symbolised the democratisation of Malaysia, we must also acknowledge the crucial role of internet media in this process - overcoming government censorship, enlightening the public, and promoting diverse political perspectives and choices. In this sense, Anwar has been the greatest beneficiary of internet freedom.

With 20 years of Reformasi experience, Anwar and his team know well how opposition parties and dissidents can leverage internet media (especially social media) to challenge official narratives and ideologies. Unsurprisingly, they are now eager to govern internet media.

It is an ironic twist of history that a government that rose to power on the back of calls for Reformasi and benefited from relatively free internet media, is now more committed than its predecessors to regulating internet media and shrinking the online public sphere.

This is the political reality. In a country where mainstream media is tightly controlled, opposition parties must rely on internet media to engage with their target audiences. They criticise the legislation and enforcement of restricting online spheres.

Justifying control over freedom of expression

However, once in power, the opposition often becomes the government it once criticised, intent on controlling the political instruments and platforms the opposition might use to compete with them.

Those in power always justify their measures to restrict free speech and public discourse by citing noble reasons, such as maintaining racial harmony, social order, curbing disinformation and misinformation, and protecting children.

These politically correct justifications often garner support, including academics and lawyers who believe in resorting to the law for every issue.

Since taking office, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s coalition government has been keen to regulate the internet and social media. Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil has met with social media representatives to “discuss content regulation”.

Subsequently, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) announced that all social media and internet messaging services with at least eight million registered users in Malaysia must apply for an Applications Service Provider Class Licence under the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 (Act 588) by Jan 1, 2025. One of the requirements to obtain this licence is using locally incorporated companies.

Fahmi also revealed that a bill to amend laws on cyberbullying might be tabled in the current Parliament session to clarify the definition of cyberbullying and increase penalties. The government is considering banning children under 13 from having social media accounts.

In addition, Fahmi recently disclosed that the MCMC is set to announce the code of conduct for social media platform providers and that providers will need to abide by the code once the Class Licence for Application Service Providers comes into force on Jan 1.

Onus on platform providers to moderate content

At the time of writing, the code of conduct for social media platform providers has yet to be published. However, according to Fahmi, once the class licence takes effect on Jan 1, providers will need to adhere to this code. This move not only regulates social media content but also shifts the responsibility of content moderation to service providers.

The concern here is that to avoid being reprimanded by the government for not complying with the code, social media platform owners might over-censor content, severely limiting the diversity of online discourse.

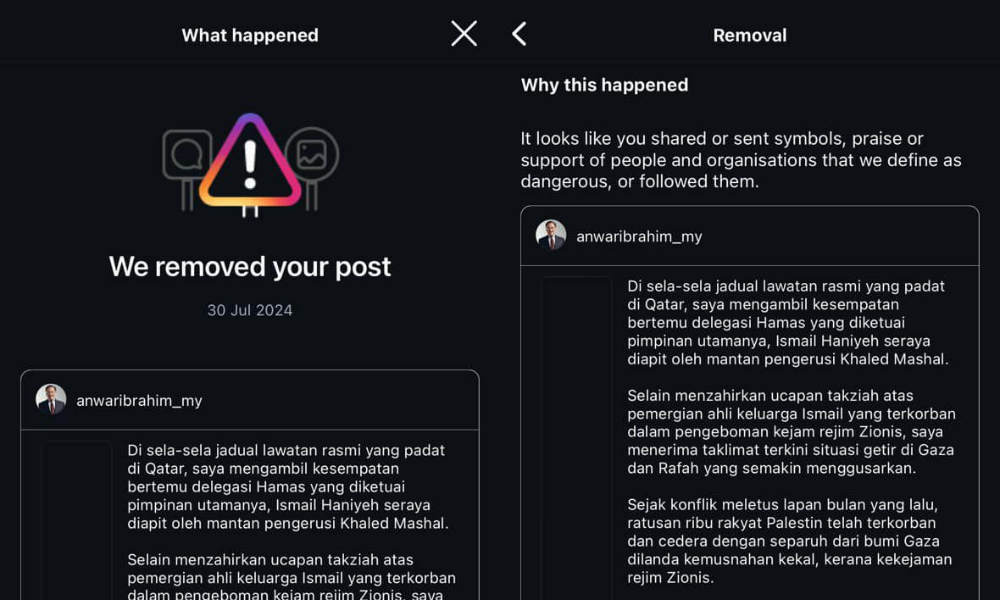

A recent example shows that this concern is not unwarranted. On July 31, Anwar posted a video recording of his phone call with a Hamas official to offer condolences on his Facebook account, but it was later removed by the social media platform. A similar post on his Instagram account was also taken down, accompanied by the caption “Dangerous individuals and organisations”.

The government was furious and summoned representatives of Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, to demand an explanation and apology. Meta quickly restored Anwar’s post and issued a public apology.

This incident provides two key reflections:

Firstly, while people vehemently oppose government censorship and suppression of free speech online, social media companies are already acting as global gatekeepers to police freedom of speech, deciding which political views are permissible in the internet marketplace of ideas.

If we oppose government censorship, we should not uncritically accept the power of social media platforms to police free speech. If the prime minister himself faces such treatment, what can ordinary internet users expect?

Secondly, Meta’s restoration of Anwar’s post and its apology occurred because the so-called “victim” of this censorship was the head of the government, not an ordinary social media user.

Social media and govt interests

Although Malaysia is not a superpower, and social media giants have had confrontations with superpowers, they likely prefer not to provoke governments unnecessarily. Instead, they tend to appease those in power.

How can we ensure that social media platforms do not serve the political interests of the ruling party (whichever it may be) by restricting citizens’ free speech or removing opinions deemed undesirable by the government?

These are risks that those hastily advocating for legal solutions must consider. At the same time, we must also ask: are the government’s measures to regulate social media also addressing state-sponsored disinformation?

CHANG TECK PENG is a journalist-turned-academic and leads the postgraduate programmes in Communication at the Tunku Abdul Rahman University of Management and Technology. His research focuses on the political economy of communication, communication law and policies, press freedom, internet media and Chinese-medium media.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable