COMMENT | Limits of the RCEP

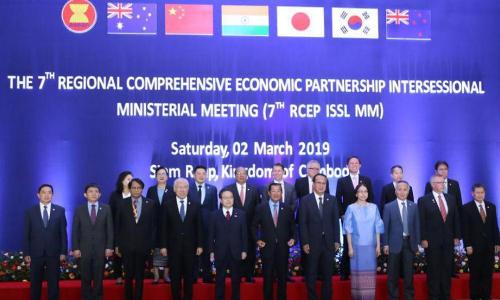

COMMENT | Last month, 15 Asia-Pacific countries signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. The occasion marked what might be the most significant economic achievement since the Covid-19 crisis began. And yet the RCEP – or, indeed, Asia – cannot save the ailing multilateral trading system alone.

To be sure, the RCEP is a firm repudiation of the protectionism that has been gaining ground in recent years. Economic integration is very difficult in the Asia-Pacific, owing to widely varying levels of development, diverse cultures and institutional structures, and ongoing territorial disputes. But, confronted with the Covid-19 downturn, the parties were eager to conclude the pact, after eight years of negotiations.

And this is no minor trade bloc. Signatories include China and Japan – the world’s second and third-largest national economies, respectively – as well as South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and ten Southeast Asian countries. The RCEP thus accounts for 30 percent of global GDP, making it the world’s largest free-trade area.

Moreover, the pact is a major step forward for regional economic integration. Signatories will eliminate various tariffs on imported goods, align trade norms, and adhere to unified rules-of-origin standards. The agreement also includes provisions on intellectual property, government procurement, financial services, and e-commerce.

But the RCEP has its limits. It lacks ...

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable