COMMENT | A mislaid path for PAS

COMMENT | The existing arrangement of Muafakat Nasional between PAS and Umno is not as straightforward as one plus one equals two. There’s more to this than meets the eye.

As a political science student researching PAS and later as a politician working closely with PAS leaders, I often lamented at PAS’s missed opportunities to change the course of Malaysian political history. Perhaps, it is the story of the mislaid path for PAS.

From the 1999 general election until the break-up between PAS and Pakatan Rakyat in June 2015, there had been two broad strands of thoughts in PAS. One I call the purists and the other one the mainstreamers.

The purists were only interested to secure the Malay heartlands – Kelantan, Terengganu, Kedah and Perlis – with their literal and sometimes homegrown interpretation of Islam. They were not interested in winning votes from non-Muslims and were happy to break up any national coalitions that required compromises.

The mainstreamers, a term used by the late PAS president Ustaz Fadzil Noor in one of his muktamar speeches, emerged from the 1999 general election when party candidates with professional qualifications won a number of parliamentary seats outside Kelantan and Terengganu.

It was also an indication of PAS’s potential in winning federal government with a multi-ethnic coalition. The party won 27 parliamentary seats riding on Anwar Ibrahim’s reformasi wave.

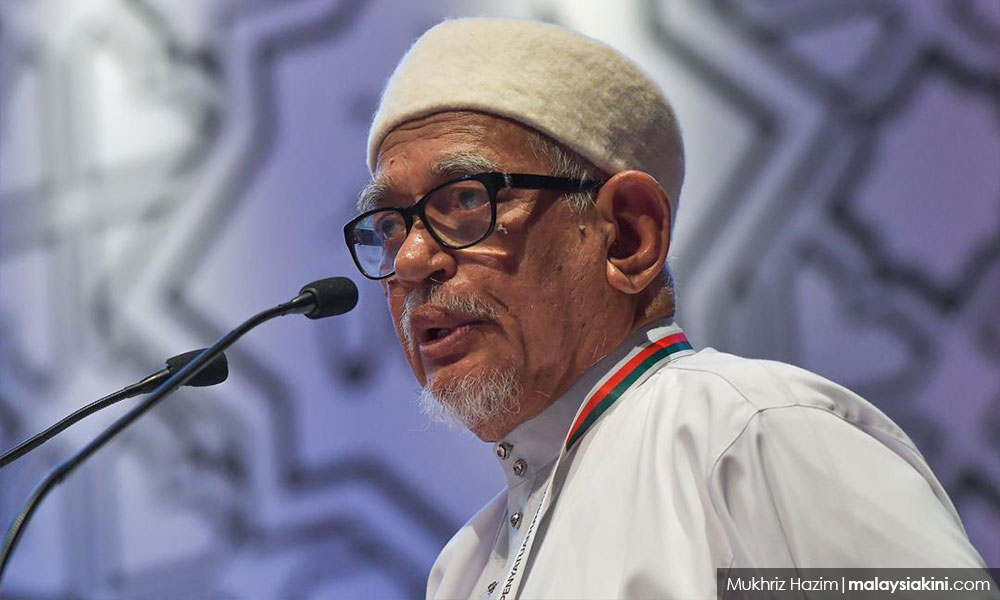

However, the mainstreamers suffered a setback with the passing of Fadzil in June 2002. Ustaz Abdul Hadi Awang who succeeded him endorsed a hard-line approach. In the run-up to the March 2004 general election, the party offered voters the “Islamic State Document” which was launched in November 2003. PAS was rejected nationally.

Subsequently, the mainstreamers had a slight upper hand though it was never easy for them in the years between 2005 and 2013.

The original purists who came to the fore in the 1982 coup against the then party president Asri Muda, were now reinforced by a new generation of hardliners. For some reason they found it easy to get close to the then prime minister Najib Abdul Razak’s people after the 2013 general election.

The demise of Tok Guru Nik Aziz – the arbiter of internal divisions – on Feb 12, 2015, finally removed the hurdle for those who had been clamouring to align with Najib and Umno amid the 1MDB mega-scandal.

The mainstreamers were annihilated in the party election at the 2015 muktamar. The new pro-Umno purist leadership resolved to break off cooperation with the DAP in Pakatan Rakyat.

With the demise of Pakatan Rakyat, Parti Amanah Nasional was formed by former PAS members and leaders on Sept 16, 2015, followed by the formation of Pakatan Harapan on Sept 22, 2015.

The cooperation between PAS and Umno during 2014-18 culminated in PAS contesting as a spoiler in the last general election. When BN lost for the first time in history, the two Malay parties decided to formalise their Muafakat Nasional in 2019, thus repudiating PAS’ struggles in the preceding years since 1982.

1. From anti-assabiyah to Malay-first

The idea of kepimpinan ulama (leadership by religious scholars) was the battle cry in 1982 to differentiate the new leadership from the old Asri’s Malay-first rhetoric – the era when Malays saw PAS as a party for orang kampung. The new leadership in 1982 embraced the slogan of against assabiyah (race-based nationalism) – referring to Umno as a secular nationalistic Malay party that must be crushed.

2. From anti-Umno to embracing Umno

At the same time, the Terengganu group of the 1982 generation led by Hadi Awang pushed a very sharp divide to differentiate PAS from Umno. In an almost sectarian-like division, PAS members would not pray when an Umno imam would lead the prayer, instead, they held separate prayers. With such a painful experience, the only excuse they give for PAS and Umno to work together now is the claim that they are fighting the so-called DAP and non-Malay domination. This is quite dubious because many PAS grassroots had good relationships with DAP members under Pakatan Rakyat, as well as organising Bersih rallies, between 2008 and 2015.

3. Images of Islam in politics

The year 1982 was a pivotal moment in Malay politics. Not only did PAS have a new leadership, but Umno under new prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad also brought in Abim president Anwar Ibrahim to give Umno an Islamic boost. The young Turks of PAS, particularly Fadzil Noor and Hadi Awang were also from Abim too. Effectively, the Islamic revival of the 1970s was represented on both the government and opposition sides. In 1982, Islamic symbols were supposed to be powerful enough to convince many Malay Muslims to give political support to either side.

Today, however, the Muslim community is much more sophisticated. To tell someone sukuk – the product of Islamic finances – is good is not sufficient. The moment sukuk is used for siphoning money off from 1MDB, at least half of the Muslim population would not accept a corrupt deal as halal, whatever name you call it.

There is no way PAS can legitimise Najib’s financial crimes against the nation. It is also painful for PAS grassroots to work with Umno that is still dominated by people of dubious records as far as financial scandals are concerned.

Today many clichés are being recycled in Malaysian political commentaries. The oft-repeated claim is that the combined votes PAS and Umno received in the 2018 election would have thwarted Pakatan Harapan’s victory in GE14.

The first thing I learned from my thesis supervisor John Funston back in 2002 when I started researching on PAS was that for many elections PAS usually received about 30 percent of Malay votes. Most of them voted for PAS not because they like PAS but they were against Umno and BN for whatever reason.

The same rule still applied in 2018. The hundreds of thousands from Kuala Lumpur that returned to their respective hometowns in Terengganu and Kelantan voted for PAS because they believed the Islamist party had a higher chance of defeating Najib’s candidates. They didn’t necessarily love PAS.

There were just like Semenanjung’s west coast people who voted for Pakatan Harapan simply because they wanted to kick BN out. The last GE was an anti-Najib and anti-kleptocracy election.

Today, most of the voters who chose PAS in GE14 may not vote for Umno as well as PAS if Umno is still led by Ahmad Zahid Hamidi, Najib Abdul Razak and Tengku Adnan Mansor – all of them facing multiple corruption charges.

The Muafakat Nasional strategy is not an election strategy. It was an attempt to rile up racial sentiments against Pakatan Harapan. To the Malays, they said the DAP controlled the government and to the non-Malays, they alleged Mahathir controlled everything. The purpose was to burn the house down and cause the breakup of Harapan from the middle.

PAS would have a tough time winning the next election. After discarding the spirit of 1982, the party is now under the spell of Zahid and Najib, embracing the very thing they hate for almost 40 years. It is indeed a mislaid path for PAS.

Thus, one plus one – PAS and Umno – doesn’t necessarily equal two.

LIEW CHIN TONG is a senator and ex-deputy defence minister.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable