COMMENT | 377: The law that changed Msia's political history forever

COMMENT | Some may remember Malaysia as a nation with a one-time penchant for projecting its record-achieving feats.

In 2019, under the Pakatan Harapan government, the country inadvertently returned under this spotlight with not one but two episodes where Section 377A of the Penal Code (Act 574) - the law that criminalises "carnal intercourse against the order of nature" - was invoked, yet again, upon then prime ministerial contenders Anwar Ibrahim and Azmin Ali.

Few could have predicted that this legislation would rear its ugly head so soon after the momentous (but short-lived) regime change, just over a year after Harapan swept into power with promises of being a better and cleaner government, and where for a third time, Anwar faced déjà vu accusations of "unnatural sex", but not before similar charges were levied at Azmin - his former protégée, now rival - several months earlier.

It’s interesting to note that 377, as the legislation is now commonly known, was given to us by the British. How then did this law, a colonial imposition, gain so much influence over our country’s history?

Origins of 377

Before it gained such infamy, not many had heard of 377. Sodomy had barely been prosecuted in Malaysia prior to the Anwar trial in 1998.

Moreover, between 1990-2010, the overwhelming majority of men who were charged in court were those who had engaged in anal or oral sex with children, rather than men in consensual same-sex relations. In other words, the law was largely flexed upon adults involved in coercive or underaged anal or oral sex, ie anal or statutory rape; not on consenting adults.

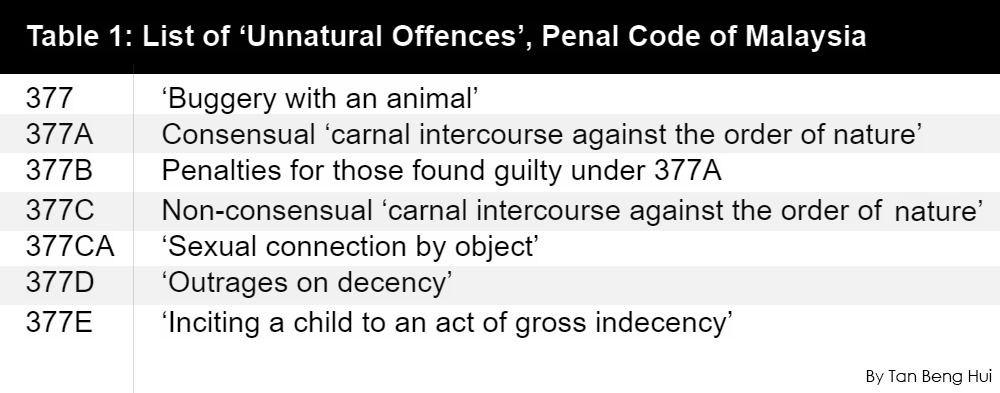

Adopted with the rest of the 1860 Indian Penal Code - which the British first enacted there and used as a legal template for its other colonies later - today’s Section 377A is a refined version of the originally crafted 377 (see Table 1 below).

The latter was framed to punish "whoever voluntarily had carnal intercourse against the order of nature with any man, woman, or animal" (Penal Code Ordinance, No. 14 of 1871). It targeted penetrative sex involving the penis and anus or mouth, whether this was between a man and another man, woman or animal.

In short, its focus was on the abnormality of such sex, not the prohibition of male homosexual relations or identities per se. The popular association between 377 and gay men today is thus a curious one.

The question of why and how this linkage happened is outside the scope of this article and deserves a separate discussion. Suffice to say, it is more helpful to understand the introduction of 377 not solely as a piece of legislation to prohibit these kinds of sexual acts but as part of a broader set of morality laws that British rule instituted for a variety of reasons.

For one, the combination of viewing the colonised populace as inferior subjects and the belief that the tropics were a hotbed for licentious sexual behaviours and acts, including sodomy, was justification enough to embark on a Christian civilising mission.

This, it was said, would promote sexual restraint amongst both the "natives" and "white men", the latter whom the crown feared might succumb to moral lapses. Section 377, however, was only one of a number of laws introduced for this purpose. The Penal Code also contained clauses to regulate "immoral" acts like "obscenity" and "prostitution".

Upholding this morally virtuous stance hid those in the colonies from the reality of Victorian England, where beneath the veneer of sexual purity and moral righteousness was a society thriving with all kinds of sexualities and erotic activities that the authorities rejected.

Worse perhaps, British expansion introduced "guilty inhibitions about sex into societies previously much better sexually adjusted than perhaps any in the West", according to professor Ronald Hyam.

Certainly, evidence shows the Malay archipelago as accepting of those with non-binary sexualities and genders in precolonial times. One wonders what Malaysia would be like today had it continued on this trajectory, free from British intervention.

The entry of such moral regulations appears tied to a desire to prevent interracial sexual relations as well. Regardless of whether these were homosexual or heterosexual, liaisons of this nature were viewed as dangerous due to their potential to blur distinctions between "white" and "non-white", ruler and ruled, and hence put colonial authority at risk.

This may explain why marriages between white men and native women were hardly encouraged even though such intimate relationships were not uncommon in British Malaya. Projecting a facade of white superiority was a paramount consideration at the time.

Moving on from 377

The dubious colonial origins of Section 377A is reason enough to ask why Malaysia continues to have this relic piece of legislation on its statute books today. One obvious explanation would be that it has proven to be a convenient and easy tool to use against political foes.

This, however, should be a reason to abolish the law, not leave it unchallenged. Another less obvious explanation, and one worthy of more query, is related to how sex and sexuality - along with gender diversity - continue to be narrowly understood in this country.

Like the nineteenth century, heteronormative conceptions dominate what constitutes acceptable sexual relations and acts today - with sex within heterosexual marriage the most privileged - rendering those who fall outside these boundaries at risk of being labelled "abnormal" or "deviant".

Indeed, growing intolerance here means that such labels are not just useful to eliminate political competition but are also engaged to harass, extort or limit the public participation and representation of LGBT people and people of diverse genders and sexualities, or worse, to threaten and endanger their lives.

Rather than question the colonial basis for criminalising "unnatural sex", lawmakers in post-independence Malaysia further expanded and strengthened its ambit.

In 1989, Parliament responded to pressure by women’s groups to expand the definition of rape in the Penal Code to cover anal rape. However, for reasons never made public, it criminalised this under 377, not Section 375 on rape.

The same logic behind this decision was repeated in 2004 when the act of using an object to rape a person was also prohibited under 377. Presumably, this had to do with how some could not fathom sex as anything besides heterosexual penile penetration of the vagina. That they chose to categorise these as "unnatural offences" rather than forced sex, ie rape, is telling.

Also telling has been the decision to impose harsher penalties as a deterrent. In the 1989 reforms, the maximum jail time for sodomy was raised from 10 to 20 years. Similarly, when mandatory whipping was added to the penalties under Sections 377B and 377C in conjunction with the adoption of the Sexual Offences Against Children Act 2017.

This lack of distinction between the punishments for consensual and non-consensual sexual relations - the only difference being the minimum five-year jail sentence for the latter - is very problematic and highlights the challenges around dislodging deeply embedded colonial notions of "proper" (read: "natural" and "normal") sex.

Given this history and misconceptions around 377, it is critical to encourage more dialogues on how the hierarchy of sexualities and genders has evolved (ie who decided what was acceptable and why, as well as how these decisions were enforced), and if left unaddressed, what the impact of maintaining this hierarchy will be on the long-term wellbeing of the nation.

This would be especially timely in light of the largely positive developments across the globe where an increasing number of states are recognising the need to modernise, reform or repeal such legislation.

TAN BENG HUI is an independent researcher who works on issues of gender, sexuality and development in Malaysia. This article was produced in collaboration with Queer Lapis.

The views expressed here are those of the author/contributor and do not necessarily represent the views of Malaysiakini.

Keep up with the latest information on the outbreak in the country with Malaysiakini's free Covid-19 tracker.

Malaysiakini is providing free access to the most important updates on the coronavirus pandemic. You can find them here.

Help keep independent media alive - subscribe to Malaysiakini.

RM12.50 / month

- Unlimited access to award-winning journalism

- Comment and share your opinions on all our articles

- Gift interesting stories to your friends

- Tax deductable